8 December 2013

It was an inspiration to be with a large group of weavers at the national gathering that I wrote about in the last post, and to talk with them about different weaving projects they were working on. Here are just a few of the weavers I spoke to.

Jute, cotton and raffia aren’t traditionally used in Māāri weaving but these materials were being used by Lisa Smith from Ahipara to weave a cloak for one of her sons. Lisa used jute for the warp threads and a finer cotton for twining the weft threads. Black tags made from raffia found in a $2 shop were added as the twining progressed and decorative panels were made with the addition of coloured tail feathers from a rooster. Lisa used a frame to support the weaving and added the feathers upside down so that they didn’t get in the way of the weaving. Being a busy mum, Lisa has overcome the time consuming task of preparing materials with her imaginative use of bought threads.

Jute, cotton and raffia aren’t traditionally used in Māāri weaving but these materials were being used by Lisa Smith from Ahipara to weave a cloak for one of her sons. Lisa used jute for the warp threads and a finer cotton for twining the weft threads. Black tags made from raffia found in a $2 shop were added as the twining progressed and decorative panels were made with the addition of coloured tail feathers from a rooster. Lisa used a frame to support the weaving and added the feathers upside down so that they didn’t get in the way of the weaving. Being a busy mum, Lisa has overcome the time consuming task of preparing materials with her imaginative use of bought threads.

Paretio Ruha from Waihau Bay chose the legend of the creation of pīngao as the inspiration for the cloak, or rapaki, she was weaving as part of her studies of Māori art at Te Wananga o Aotearoa Rahui Pokeka in Huntly. In the legend, Tangaroa, God of the sea, was angry with his brother Tane, God of the Forest, for separating their parents Papatuanuku and Ranginui. To appease Tangaroa, Tane offered him his eyebrows. Tangaroa became angry at this offer and threw the eyebrows back up onto the beach where they sprouted and grow today as pīngao. Paretio has used blues and yellows in her cloak to symbolise the realms of water and land, purple to represent seaweed, and has plaited yellow curls to symbolise the eyebrows.

Paretio Ruha from Waihau Bay chose the legend of the creation of pīngao as the inspiration for the cloak, or rapaki, she was weaving as part of her studies of Māori art at Te Wananga o Aotearoa Rahui Pokeka in Huntly. In the legend, Tangaroa, God of the sea, was angry with his brother Tane, God of the Forest, for separating their parents Papatuanuku and Ranginui. To appease Tangaroa, Tane offered him his eyebrows. Tangaroa became angry at this offer and threw the eyebrows back up onto the beach where they sprouted and grow today as pīngao. Paretio has used blues and yellows in her cloak to symbolise the realms of water and land, purple to represent seaweed, and has plaited yellow curls to symbolise the eyebrows.

Bev Vellenoweth from Ōpotiki specialises in weaving with fine fibre, or muka, creating tiny baskets like the one shown here inside a paua shell. She uses fine jewellery wire for a twining thread to hold the fibre together, and to give structure and shape to the article she is making. Bev’s entry in the fashion show featured a dress with a fine fibre bodice and a skirt made with thin flax cylinders dyed a pretty soft green. Bev uses both naturally coloured and dyed fibre to make her little baskets which she exhibits widely and has won a number of awards for.

Bev Vellenoweth from Ōpotiki specialises in weaving with fine fibre, or muka, creating tiny baskets like the one shown here inside a paua shell. She uses fine jewellery wire for a twining thread to hold the fibre together, and to give structure and shape to the article she is making. Bev’s entry in the fashion show featured a dress with a fine fibre bodice and a skirt made with thin flax cylinders dyed a pretty soft green. Bev uses both naturally coloured and dyed fibre to make her little baskets which she exhibits widely and has won a number of awards for.

Karl Leonard is an experienced skirt, or piupiu, maker and well used to preparing flax strips for these garments. Using a long ruler marked at different lengths as a guide, he cuts the flax halfway through on the back of the strips at each guide mark. Next he separates the green flesh of the leaf from the fibre in between the cut parts on the leaf. Karl advises that when preparing strips for patterning in this way, it’s important to keep the leaves damp as the fleshy part strips off much easier when the leaves are moist. To complete the preparation for piupiu making, the strips are boiled and hung up to dry where they curl into cylinders. The strips are then ready to be braided onto the waistband and dyed. When flax prepared in this way is dyed, the dye adheres to the fibre and not to the unscraped flax, making dyed and undyed blocks on the cylindrical strips which create the pattern.

Karl Leonard is an experienced skirt, or piupiu, maker and well used to preparing flax strips for these garments. Using a long ruler marked at different lengths as a guide, he cuts the flax halfway through on the back of the strips at each guide mark. Next he separates the green flesh of the leaf from the fibre in between the cut parts on the leaf. Karl advises that when preparing strips for patterning in this way, it’s important to keep the leaves damp as the fleshy part strips off much easier when the leaves are moist. To complete the preparation for piupiu making, the strips are boiled and hung up to dry where they curl into cylinders. The strips are then ready to be braided onto the waistband and dyed. When flax prepared in this way is dyed, the dye adheres to the fibre and not to the unscraped flax, making dyed and undyed blocks on the cylindrical strips which create the pattern.

It was good to meet Felicity Champion at the gathering as we have corresponded over the years and Felicity has promoted my book to her weaving students. Felicity brought along a basket that she had woven using two different greens to make the pattern. Using colour in this way is very attractive and results in a subtle, natural blend of colours that I find very pleasing to the eye. Felicity’s basket caught many people’s admiring attention as they passed by.

It was good to meet Felicity Champion at the gathering as we have corresponded over the years and Felicity has promoted my book to her weaving students. Felicity brought along a basket that she had woven using two different greens to make the pattern. Using colour in this way is very attractive and results in a subtle, natural blend of colours that I find very pleasing to the eye. Felicity’s basket caught many people’s admiring attention as they passed by.

Marie Flavell’s choice of weaving was a circular piece which she started and completed over the weekend. She started with a plait, adding in a number of red, black and natural coloured strips in a particular sequence and, as she wove, a pleasing flower-like pattern emerged. To make a circular piece like this, add the strips to the plait two or four at a time, overlapping them as they are added. This allows for the weaving to be curled around. Marie mentioned that her favourite weaving flax is Raumoa as she finds it soft and supple to weave with. Landcare Research describe this cultivar as having soft leaves with a good fibre content, and which dries to a very white colour when boiled.

Marie Flavell’s choice of weaving was a circular piece which she started and completed over the weekend. She started with a plait, adding in a number of red, black and natural coloured strips in a particular sequence and, as she wove, a pleasing flower-like pattern emerged. To make a circular piece like this, add the strips to the plait two or four at a time, overlapping them as they are added. This allows for the weaving to be curled around. Marie mentioned that her favourite weaving flax is Raumoa as she finds it soft and supple to weave with. Landcare Research describe this cultivar as having soft leaves with a good fibre content, and which dries to a very white colour when boiled.

Chris Bradshaw from Matata, a guest of honour at the gathering, has specialised in weaving hats, or pōtae and it was interesting to see the different style of hat that Chris wore each day. The hat pictured here is started at the crown using a method that is often seen for the start of the base of a container with pointed feet, in weaving from Asia. Another of Chris’s hats was woven with pīngao leaves, the fluted ends of the pīngao leaf, where it is pulled from the plant, being used as a decorative feature at the edge of the brim. I enjoyed seeing the variety of hats that Chris had woven and plan to make a hat for myself over the Christmas break.

Chris Bradshaw from Matata, a guest of honour at the gathering, has specialised in weaving hats, or pōtae and it was interesting to see the different style of hat that Chris wore each day. The hat pictured here is started at the crown using a method that is often seen for the start of the base of a container with pointed feet, in weaving from Asia. Another of Chris’s hats was woven with pīngao leaves, the fluted ends of the pīngao leaf, where it is pulled from the plant, being used as a decorative feature at the edge of the brim. I enjoyed seeing the variety of hats that Chris had woven and plan to make a hat for myself over the Christmas break.

Meeting other weavers at a national gathering and seeing the different items they are creating with their weaving is both educational and inspirational. I would suggest to anyone interested in flax weaving that it would be worth attending the next national weavers’ gathering to be held in Ahipara in 2015. For information contact Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa.

© Ali Brown 2013.

Scroll down to leave a new comment or view recent comments.

Also, check out earlier comments received on this blog post when it was hosted on my original website.

Eighteen people, coming from Okains Bay, Decanter Bay, Charteris Bay, Pines Beach, Loburn and Havelock as well as Christchurch, took part in our charity flax weaving workshop last Sunday. As usual for a workshop, there were beginners and experienced weavers attending, which is a great mix as experiences are shared and people help each other. Most people wove a two-cornered basket or kete and a couple of people tried their hand at the open-weave basket made with the kupenga or fishing net weave illustrated here. Later in the day people had time to make large containers.

Eighteen people, coming from Okains Bay, Decanter Bay, Charteris Bay, Pines Beach, Loburn and Havelock as well as Christchurch, took part in our charity flax weaving workshop last Sunday. As usual for a workshop, there were beginners and experienced weavers attending, which is a great mix as experiences are shared and people help each other. Most people wove a two-cornered basket or kete and a couple of people tried their hand at the open-weave basket made with the kupenga or fishing net weave illustrated here. Later in the day people had time to make large containers. There were three different types of splitting tools in use in the workshop, apart from awls and fingernails! Sharon’s splitting tools, which were originally used for shearing sheep, had been modified with the addition of a paua-inlaid wooden handle.

There were three different types of splitting tools in use in the workshop, apart from awls and fingernails! Sharon’s splitting tools, which were originally used for shearing sheep, had been modified with the addition of a paua-inlaid wooden handle. My splitting tools were made by my husband Rob using bodkins inserted into blocks of wood at equal distances. Kay’s were very original, being made from corn cob holders. Kay adjusts the distance between the prongs depending on the width of strips she requires.

My splitting tools were made by my husband Rob using bodkins inserted into blocks of wood at equal distances. Kay’s were very original, being made from corn cob holders. Kay adjusts the distance between the prongs depending on the width of strips she requires.

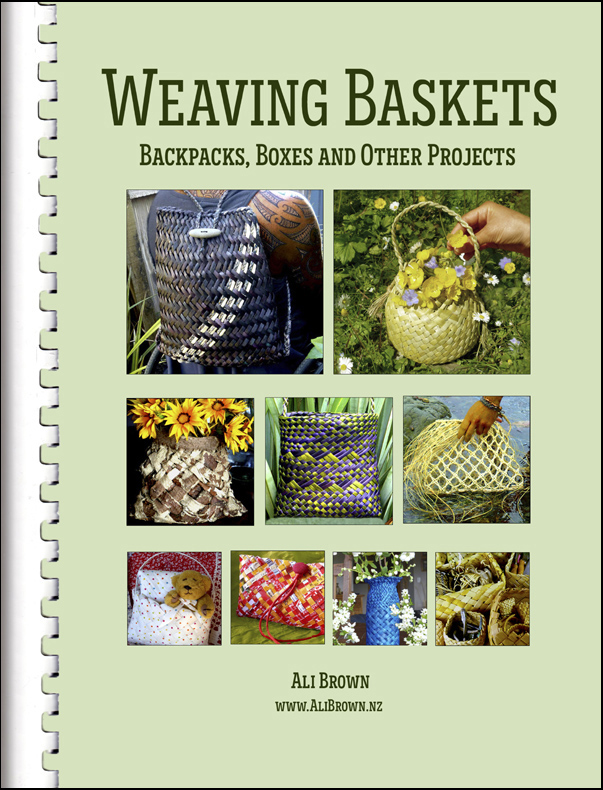

The book I’ve been writing, Weaving Baskets, Backpacks, Boxes and Other Projects, is now ready for sale. This book covers a comprehensive range of basket-making, starting from instructions for a simple woven folded-over basket to complex patterned baskets and backpacks, as well as boxes, platters, trays, vases and pots. Each project has illustrated instructions and colour photos that show step-by-step instructions for weaving, using diagonal weaving. Over 70 different techniques and methods used in basket-making are included.

The book I’ve been writing, Weaving Baskets, Backpacks, Boxes and Other Projects, is now ready for sale. This book covers a comprehensive range of basket-making, starting from instructions for a simple woven folded-over basket to complex patterned baskets and backpacks, as well as boxes, platters, trays, vases and pots. Each project has illustrated instructions and colour photos that show step-by-step instructions for weaving, using diagonal weaving. Over 70 different techniques and methods used in basket-making are included. Most of the samples in the book are woven with New Zealand flax but any natural or manufactured material that can be made into long thin strips can be used, including palm leaves, strapping, bark and paper, like the basket illustrated here which is made with strips of packaging.

Most of the samples in the book are woven with New Zealand flax but any natural or manufactured material that can be made into long thin strips can be used, including palm leaves, strapping, bark and paper, like the basket illustrated here which is made with strips of packaging. The book has instructions for traditional Māori weaving techniques such as the ones used to weave the backpack with the stone toggle illustrated here. As well as instructions for weaving backpacks, several different ways of weaving larger baskets are described in the book, including starting at the base with a plait, starting at the top with a plait and starting in the middle with a cylinder.

The book has instructions for traditional Māori weaving techniques such as the ones used to weave the backpack with the stone toggle illustrated here. As well as instructions for weaving backpacks, several different ways of weaving larger baskets are described in the book, including starting at the base with a plait, starting at the top with a plait and starting in the middle with a cylinder. More modern weaving ideas are also included in the book. The rounded-shaped basket illustrated here is reminiscent of other traditional styles of baskets, such as those seen in UK, Europe and USA. Instructions for making different types of basket handles, like the twisted one on this basket, are also included. Other projects give instructions for weaving more contemporary items like vases and pots, as well as serving platters and boxes.

More modern weaving ideas are also included in the book. The rounded-shaped basket illustrated here is reminiscent of other traditional styles of baskets, such as those seen in UK, Europe and USA. Instructions for making different types of basket handles, like the twisted one on this basket, are also included. Other projects give instructions for weaving more contemporary items like vases and pots, as well as serving platters and boxes. The book has new techniques to be learned in each project and so is also suitable for a course book as well as for individual weavers and groups. More illustrations from the book are shown on

The book has new techniques to be learned in each project and so is also suitable for a course book as well as for individual weavers and groups. More illustrations from the book are shown on  The book can be purchased directly from me through my

The book can be purchased directly from me through my  In Māori tradition, the first piece of flax weaving a beginner completes is given away and the giving of flax gifts extends this tradition. Weaving flax gifts can be both satisfying and fun and makes for both economical and very acceptable gifts. There are all sorts gifts that can be made with flax and this includes gifts for pets as well as people. A round basket, made using the technique of weaving a large container, which is explained and illustrated in my book

In Māori tradition, the first piece of flax weaving a beginner completes is given away and the giving of flax gifts extends this tradition. Weaving flax gifts can be both satisfying and fun and makes for both economical and very acceptable gifts. There are all sorts gifts that can be made with flax and this includes gifts for pets as well as people. A round basket, made using the technique of weaving a large container, which is explained and illustrated in my book  Flaxworks can also be used instead of wrapping paper as the container for a gift. When two of my long-standing work colleagues resigned, bone carvings from master carver

Flaxworks can also be used instead of wrapping paper as the container for a gift. When two of my long-standing work colleagues resigned, bone carvings from master carver  Flaxwork gifts are regularly used to represent the relationship between two organisations or groups of people. The agency where I work has a close working relationship with a Māori social service agency and to represent the two baskets of knowledge which each organisation brings to the partnership, I wove two little ketes and joined them together. These were gifted to the other organisation, the staff and clients acknowledged the representation and were delighted to accept the gift. The ketes are held together with a flax strip looped around a small flax button.

Flaxwork gifts are regularly used to represent the relationship between two organisations or groups of people. The agency where I work has a close working relationship with a Māori social service agency and to represent the two baskets of knowledge which each organisation brings to the partnership, I wove two little ketes and joined them together. These were gifted to the other organisation, the staff and clients acknowledged the representation and were delighted to accept the gift. The ketes are held together with a flax strip looped around a small flax button. Flax flower bouquets make a welcome thank-you gift for a guest speaker. These flowers are woven with variegated flax and dyed red. The whiter parts of the variegated flax dyed a different red from the greener parts, which give the flowers an interesting twist. These soft multi-coloured flax varieties aren’t usually used for weaving but their softness is fine for flowers and makes them easier to weave. Information about netted flax is on my page

Flax flower bouquets make a welcome thank-you gift for a guest speaker. These flowers are woven with variegated flax and dyed red. The whiter parts of the variegated flax dyed a different red from the greener parts, which give the flowers an interesting twist. These soft multi-coloured flax varieties aren’t usually used for weaving but their softness is fine for flowers and makes them easier to weave. Information about netted flax is on my page  A paua-shell kete can be very acceptable as a gift, particularly for people from other countries. It gives the recipient a taste of the culture of New Zealand, and always seems to be well received. I’ve made paua kete in several different styles, including one with a long fringe illustrated here, and a more wrapped-around version shown in my blog post

A paua-shell kete can be very acceptable as a gift, particularly for people from other countries. It gives the recipient a taste of the culture of New Zealand, and always seems to be well received. I’ve made paua kete in several different styles, including one with a long fringe illustrated here, and a more wrapped-around version shown in my blog post  However the tradition of giving the first piece of weaving away originated, it reflects the fact that weaving flax is not just a personal accomplishment but relies on a whole body of knowledge, experience and tradition that has been passed down through many generations and is part of the culture of giving. This photo shows a flax flower symbolising the love between two people, in this case a father and daughter — and as it’s one of the last photos I have of my late father, it holds a special meaning for me.

However the tradition of giving the first piece of weaving away originated, it reflects the fact that weaving flax is not just a personal accomplishment but relies on a whole body of knowledge, experience and tradition that has been passed down through many generations and is part of the culture of giving. This photo shows a flax flower symbolising the love between two people, in this case a father and daughter — and as it’s one of the last photos I have of my late father, it holds a special meaning for me. Each year in New Zealand, as ANZAC day draws near, red poppies, a world-wide symbol of remembrance for people who have lost their lives in war, start to appear. Poppies are usually made from paper or cloth, and lately knitted poppies have become popular. A few years ago I wove a poppy from flax for a friend and he told me recently that he continues to wear it every ANZAC Day. I have regularly been asked about weaving flax poppies, so here is how I made the one for him.

Each year in New Zealand, as ANZAC day draws near, red poppies, a world-wide symbol of remembrance for people who have lost their lives in war, start to appear. Poppies are usually made from paper or cloth, and lately knitted poppies have become popular. A few years ago I wove a poppy from flax for a friend and he told me recently that he continues to wear it every ANZAC Day. I have regularly been asked about weaving flax poppies, so here is how I made the one for him.  I used dyed flax, one leaf of red and one leaf of black. The red leaf is woven into a Chrysanthemum, instructions for which are on pages 5-8 in my book

I used dyed flax, one leaf of red and one leaf of black. The red leaf is woven into a Chrysanthemum, instructions for which are on pages 5-8 in my book  The black leaf is woven into an small English Rose, instructions for which are on pages 27-31 in the same book. The stem of the rose is pushed through the centre of the chrysanthemum, tied around the chrysanthemum and the ends of both flowers cut off, taking care to ensure that they are not cut off so close to the flowers that they unravel. A brooch backing or safety pin is stuck to the back with tape so the poppy can be worn on clothing.

The black leaf is woven into an small English Rose, instructions for which are on pages 27-31 in the same book. The stem of the rose is pushed through the centre of the chrysanthemum, tied around the chrysanthemum and the ends of both flowers cut off, taking care to ensure that they are not cut off so close to the flowers that they unravel. A brooch backing or safety pin is stuck to the back with tape so the poppy can be worn on clothing.  A simple flax poppy can also be made with netted flax that has been dyed red. Cut a circle out of red netted flax and moisten the flax. Push it into a round container that is smaller in diameter than the round of flax is, so that it will curve the edges up to make the shape resemble poppy petals. Take the round of flax out of the container once it’s dry and attach a black button, preferably one with a shank, for the centre of the poppy. The button can be sewn onto the netted flax and a fastening attached onto the back.

A simple flax poppy can also be made with netted flax that has been dyed red. Cut a circle out of red netted flax and moisten the flax. Push it into a round container that is smaller in diameter than the round of flax is, so that it will curve the edges up to make the shape resemble poppy petals. Take the round of flax out of the container once it’s dry and attach a black button, preferably one with a shank, for the centre of the poppy. The button can be sewn onto the netted flax and a fastening attached onto the back.  If you would like to weave a poppy without having to dye the flax, you could weave a white one with the leaf from a white hybrid flax, although greenish stripes may show where the back of the flax leaf is uppermost during the folding process. The central rose in the poppy illustrated here is made with brownish/black flax. The white poppy, which used to be seen by some as unpatriotic, and perhaps still is, conveys not only remembrance but also the hope for an end to all wars.

If you would like to weave a poppy without having to dye the flax, you could weave a white one with the leaf from a white hybrid flax, although greenish stripes may show where the back of the flax leaf is uppermost during the folding process. The central rose in the poppy illustrated here is made with brownish/black flax. The white poppy, which used to be seen by some as unpatriotic, and perhaps still is, conveys not only remembrance but also the hope for an end to all wars.  January this year I tutored two flax weaving workshops at Camp Quality, which is a summer camp for children living with cancer.

January this year I tutored two flax weaving workshops at Camp Quality, which is a summer camp for children living with cancer.  I prepared the base for each wristband from the flax leaves and split the long length of the strip used to make the band into three even-width strips and the children chose the colour of their weaving strip. They wove the pattern by weaving the coloured weaver over and under the three strips all the way around which results in a checkerboard pattern as shown here.

I prepared the base for each wristband from the flax leaves and split the long length of the strip used to make the band into three even-width strips and the children chose the colour of their weaving strip. They wove the pattern by weaving the coloured weaver over and under the three strips all the way around which results in a checkerboard pattern as shown here. Some children tried weaving more complicated patterns. One used two different coloured strips as the weavers, alternating them at each turn. A couple of others were keen to try the

Some children tried weaving more complicated patterns. One used two different coloured strips as the weavers, alternating them at each turn. A couple of others were keen to try the  At camp each child has a twenty-four hour buddy who gives them one-on-one support and the wristbands turned out to be a popular choice for the buddies too, a couple of them returning to make a second one. Most people wove the first wristband for themselves and then went on to weave others for family and friends.

At camp each child has a twenty-four hour buddy who gives them one-on-one support and the wristbands turned out to be a popular choice for the buddies too, a couple of them returning to make a second one. Most people wove the first wristband for themselves and then went on to weave others for family and friends. I’ve found from past workshops that weaving wristbands is a popular project and can be woven by children from about five years upwards. The younger ones may need assistance but do tend to get into the rhythm of weaving after a while. This workshop proved how suitable wristbands continue to be for a children’s weaving workshop, as well as being of interest to all ages.

I’ve found from past workshops that weaving wristbands is a popular project and can be woven by children from about five years upwards. The younger ones may need assistance but do tend to get into the rhythm of weaving after a while. This workshop proved how suitable wristbands continue to be for a children’s weaving workshop, as well as being of interest to all ages. The same technique used to weave a pattern on wristbands can also be used to weave over the base of a handle for a basket. For example, the handle illustrated here has a

The same technique used to weave a pattern on wristbands can also be used to weave over the base of a handle for a basket. For example, the handle illustrated here has a  Earlier this year, Cosmo Kentish-Barnes of Country Life interviewed me about flax weaving and the interview was aired on Country Life on 11 and 12 July. (The interview can still be played

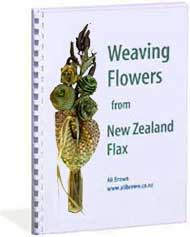

Earlier this year, Cosmo Kentish-Barnes of Country Life interviewed me about flax weaving and the interview was aired on Country Life on 11 and 12 July. (The interview can still be played  In preparation for the interview I got together some weaving we could talk about as well as my book Weaving Flowers from New Zealand Flax. Cosmo asked questions about the book, the weaving, how I became interested in weaving, how long I’d been weaving for and so on. As I’m working hard to complete my next book, on how to weave baskets, I also chattered on about that.

In preparation for the interview I got together some weaving we could talk about as well as my book Weaving Flowers from New Zealand Flax. Cosmo asked questions about the book, the weaving, how I became interested in weaving, how long I’d been weaving for and so on. As I’m working hard to complete my next book, on how to weave baskets, I also chattered on about that. This is the pot with the spiral pattern that I discussed. The pot is started with a plait at the base and the coloured strips are added in the same sequence that they are for a diagonally striped basket i.e. two crimson strips and then two natural-coloured strips alternately on each side. I then wove the sides up and rolled down the top to give the pot a strong rim. As this was an experiment to see what effect the spiral pattern would have on a pot, I used quite wide strips. I think the result is pleasing and would look even better if the pot is made with thinner strips. The black and white kete with the whitebait pattern that I talked about in the interview is illustrated on the

This is the pot with the spiral pattern that I discussed. The pot is started with a plait at the base and the coloured strips are added in the same sequence that they are for a diagonally striped basket i.e. two crimson strips and then two natural-coloured strips alternately on each side. I then wove the sides up and rolled down the top to give the pot a strong rim. As this was an experiment to see what effect the spiral pattern would have on a pot, I used quite wide strips. I think the result is pleasing and would look even better if the pot is made with thinner strips. The black and white kete with the whitebait pattern that I talked about in the interview is illustrated on the  One of the pieces of weaving that doesn’t feature in the programme but took Cosmo’s attention was the soft, muted colour of this pink bag, which is photographed side-on. I mentioned that I’ve sometimes played around with natural dyes as well as chemical dyes, and the bag was an experiment in using red wine as a dye. In the event, this bag used up six bottles of red wine, which he felt was rather a rather a waste of good wine and, in retrospect, I have to agree. I just hadn’t realised how many bottles it would take. At some point, I might try dyeing flax with the red wine skins left over from wine making to see how they turn out.

One of the pieces of weaving that doesn’t feature in the programme but took Cosmo’s attention was the soft, muted colour of this pink bag, which is photographed side-on. I mentioned that I’ve sometimes played around with natural dyes as well as chemical dyes, and the bag was an experiment in using red wine as a dye. In the event, this bag used up six bottles of red wine, which he felt was rather a rather a waste of good wine and, in retrospect, I have to agree. I just hadn’t realised how many bottles it would take. At some point, I might try dyeing flax with the red wine skins left over from wine making to see how they turn out. Another piece of weaving we talked about is this long sculptural experiment, woven with the technique that’s used for weaving a large container or waikawa. I started with six long leaves of flax that I pulled apart right down to the end of the butt, ensuring that the two sides were still joined together at the butt. I then wove the sides up as far as I could go with the lengths of the leaves, and wound the ends of the leaves that were long enough around a cylinder so they curled as they dried. Once dry I unwound them from the cylinders and they hang down like curls on a head. This was a fun piece to make although it took quite a lot longer than I expected and was a bit awkward to weave as it got longer. It’s been much appreciated by my cats, who loved climbing up it when they were kittens.

Another piece of weaving we talked about is this long sculptural experiment, woven with the technique that’s used for weaving a large container or waikawa. I started with six long leaves of flax that I pulled apart right down to the end of the butt, ensuring that the two sides were still joined together at the butt. I then wove the sides up as far as I could go with the lengths of the leaves, and wound the ends of the leaves that were long enough around a cylinder so they curled as they dried. Once dry I unwound them from the cylinders and they hang down like curls on a head. This was a fun piece to make although it took quite a lot longer than I expected and was a bit awkward to weave as it got longer. It’s been much appreciated by my cats, who loved climbing up it when they were kittens. We also talked about the types of flaxes that can be used for weaving and Cosmo wondered if the ones he saw around the garden could all be used. The flaxes that were planted here when I moved here just over two years ago are mostly ornamental and generally only good for weaving flowers. I explained that, since I moved here, I’ve planted a number of weaving flaxes from the

We also talked about the types of flaxes that can be used for weaving and Cosmo wondered if the ones he saw around the garden could all be used. The flaxes that were planted here when I moved here just over two years ago are mostly ornamental and generally only good for weaving flowers. I explained that, since I moved here, I’ve planted a number of weaving flaxes from the  The divisions I planted are now growing well around a winter pond, although they are subject to very dry conditions in summer and very wet conditions in winter. In the middle of a wet winter some of them can be completely covered apart from a little tip poking up, but the water recedes reasonably quickly over a few days, and their occasional dunking doesn’t seem to have affected their growth. When first planted in the autumn of 2012 the divisions were small stumps with cut-off leaves. They were covered in snow that winter and covered again the next winter but survived these conditions well.

The divisions I planted are now growing well around a winter pond, although they are subject to very dry conditions in summer and very wet conditions in winter. In the middle of a wet winter some of them can be completely covered apart from a little tip poking up, but the water recedes reasonably quickly over a few days, and their occasional dunking doesn’t seem to have affected their growth. When first planted in the autumn of 2012 the divisions were small stumps with cut-off leaves. They were covered in snow that winter and covered again the next winter but survived these conditions well. I spent some time in Vietnam recently enjoying the company of my eldest son and his partner as they cycle from New Zealand to Ireland. One of the ways I gain inspiration for my own weaving is by picking up ideas from other cultures, so I was particularly interested in the wide range of baskets found in everyday life in Vietnam. Bamboo, cane and rattan are the main materials used and although these have a stronger structure than NZ flax, some of the weaving ideas could be used with flax.

I spent some time in Vietnam recently enjoying the company of my eldest son and his partner as they cycle from New Zealand to Ireland. One of the ways I gain inspiration for my own weaving is by picking up ideas from other cultures, so I was particularly interested in the wide range of baskets found in everyday life in Vietnam. Bamboo, cane and rattan are the main materials used and although these have a stronger structure than NZ flax, some of the weaving ideas could be used with flax. A set of baskets that I purchased from this street vendor are typical of one of the commonest styles of baskets in Vietnam. The baskets appear to be made by weaving a square with a loose twill weave, with four or even five strips being crossed in one weave, then filling the sides with smaller strips pulled up into a semicircle, and then drawing the corners of the square together to make the bowl shape. Unique

A set of baskets that I purchased from this street vendor are typical of one of the commonest styles of baskets in Vietnam. The baskets appear to be made by weaving a square with a loose twill weave, with four or even five strips being crossed in one weave, then filling the sides with smaller strips pulled up into a semicircle, and then drawing the corners of the square together to make the bowl shape. Unique  Larger versions of the baskets I bought are often tied several baskets high on the carrier of a bike or motor scooter for transporting goods. This noodle seller piled rice noodles into large baskets, covered the wobbly piles of noodles with plastic and then tied them on his bike for delivery. He was a popular seller in the early morning as noodles are often eaten for breakfast, with rice being eaten later in the day.

Larger versions of the baskets I bought are often tied several baskets high on the carrier of a bike or motor scooter for transporting goods. This noodle seller piled rice noodles into large baskets, covered the wobbly piles of noodles with plastic and then tied them on his bike for delivery. He was a popular seller in the early morning as noodles are often eaten for breakfast, with rice being eaten later in the day. Other street vendors, selling everything from fruit and vegetables, to brooms, clothes, ceramics and cooked food, use a flatter style of basket carried on the back of a bike to display their wares. Bunches of little rose buds and other flowers are displayed to advantage on the large flat basket of this vendor. Others used the large flat baskets to hold little charcoal cooking stoves that could easily be set up anywhere for cooking food to sell. The large flax container, or waikawa, woven with whole flax leaves, can be used in a similar way to display wares, especially if the sides of the basket are kept low. (My book Weaving a Large Container from New Zealand Flax has instructions for this type of basket and can be purchased directly from me for $15, which includes postage and packaging, using direct credit as outlined on my

Other street vendors, selling everything from fruit and vegetables, to brooms, clothes, ceramics and cooked food, use a flatter style of basket carried on the back of a bike to display their wares. Bunches of little rose buds and other flowers are displayed to advantage on the large flat basket of this vendor. Others used the large flat baskets to hold little charcoal cooking stoves that could easily be set up anywhere for cooking food to sell. The large flax container, or waikawa, woven with whole flax leaves, can be used in a similar way to display wares, especially if the sides of the basket are kept low. (My book Weaving a Large Container from New Zealand Flax has instructions for this type of basket and can be purchased directly from me for $15, which includes postage and packaging, using direct credit as outlined on my  While in Hanoi I visited the Museum of Ethnology which presents the domestic culture of six of the major groups that comprise the Vietnam population. This attractive woven box caught my eye. It is has a diagonal weave and incorporates a pattern that is reminiscent of patterns used in traditional flax weaving.

While in Hanoi I visited the Museum of Ethnology which presents the domestic culture of six of the major groups that comprise the Vietnam population. This attractive woven box caught my eye. It is has a diagonal weave and incorporates a pattern that is reminiscent of patterns used in traditional flax weaving. Although it is woven from rattan, this style of box container could be woven in flax. I particularly like the way the pattern is worked on the top of the container. It appears to have been worked by weaving one quarter of the square first and then weaving the other three sides of the square around to meet back at the first one.

Although it is woven from rattan, this style of box container could be woven in flax. I particularly like the way the pattern is worked on the top of the container. It appears to have been worked by weaving one quarter of the square first and then weaving the other three sides of the square around to meet back at the first one. Again, the patterning on this basket, with its vertical and horizontal twills, could be worked as the pattern when weaving flax. In fact it’s quite likely that it’s already been used, not as a copy, but independently, as the patterns I saw in the museum are very similar to those used in traditional Maori weaving. I particularly like the way this basket is shaped.

Again, the patterning on this basket, with its vertical and horizontal twills, could be worked as the pattern when weaving flax. In fact it’s quite likely that it’s already been used, not as a copy, but independently, as the patterns I saw in the museum are very similar to those used in traditional Maori weaving. I particularly like the way this basket is shaped. I saw a variety of other types of weaving, one of the most spectacular being these fish traps stacked high onto a vendor’s bicycle. The traps, woven with thin strips of bamboo, are similar to the traditional Maori traps woven from manuka stems and supplejack vines.

I saw a variety of other types of weaving, one of the most spectacular being these fish traps stacked high onto a vendor’s bicycle. The traps, woven with thin strips of bamboo, are similar to the traditional Maori traps woven from manuka stems and supplejack vines. Jute, cotton and raffia aren’t traditionally used in Māāri weaving but these materials were being used by Lisa Smith from Ahipara to weave a cloak for one of her sons. Lisa used jute for the warp threads and a finer cotton for twining the weft threads. Black tags made from raffia found in a $2 shop were added as the twining progressed and decorative panels were made with the addition of coloured tail feathers from a rooster. Lisa used a frame to support the weaving and added the feathers upside down so that they didn’t get in the way of the weaving. Being a busy mum, Lisa has overcome the time consuming task of preparing materials with her imaginative use of bought threads.

Jute, cotton and raffia aren’t traditionally used in Māāri weaving but these materials were being used by Lisa Smith from Ahipara to weave a cloak for one of her sons. Lisa used jute for the warp threads and a finer cotton for twining the weft threads. Black tags made from raffia found in a $2 shop were added as the twining progressed and decorative panels were made with the addition of coloured tail feathers from a rooster. Lisa used a frame to support the weaving and added the feathers upside down so that they didn’t get in the way of the weaving. Being a busy mum, Lisa has overcome the time consuming task of preparing materials with her imaginative use of bought threads. Paretio Ruha from Waihau Bay chose the legend of the creation of pīngao as the inspiration for the cloak, or rapaki, she was weaving as part of her studies of Māori art at Te Wananga o Aotearoa Rahui Pokeka in Huntly. In the legend, Tangaroa, God of the sea, was angry with his brother Tane, God of the Forest, for separating their parents Papatuanuku and Ranginui. To appease Tangaroa, Tane offered him his eyebrows. Tangaroa became angry at this offer and threw the eyebrows back up onto the beach where they sprouted and grow today as

Paretio Ruha from Waihau Bay chose the legend of the creation of pīngao as the inspiration for the cloak, or rapaki, she was weaving as part of her studies of Māori art at Te Wananga o Aotearoa Rahui Pokeka in Huntly. In the legend, Tangaroa, God of the sea, was angry with his brother Tane, God of the Forest, for separating their parents Papatuanuku and Ranginui. To appease Tangaroa, Tane offered him his eyebrows. Tangaroa became angry at this offer and threw the eyebrows back up onto the beach where they sprouted and grow today as  Bev Vellenoweth from Ōpotiki specialises in weaving with fine fibre, or muka, creating tiny baskets like the one shown here inside a paua shell. She uses fine jewellery wire for a twining thread to hold the fibre together, and to give structure and shape to the article she is making. Bev’s entry in the fashion show featured a dress with a fine fibre bodice and a skirt made with thin flax cylinders dyed a pretty soft green. Bev uses both naturally coloured and dyed fibre to make her little baskets which she exhibits widely and has won a number of awards for.

Bev Vellenoweth from Ōpotiki specialises in weaving with fine fibre, or muka, creating tiny baskets like the one shown here inside a paua shell. She uses fine jewellery wire for a twining thread to hold the fibre together, and to give structure and shape to the article she is making. Bev’s entry in the fashion show featured a dress with a fine fibre bodice and a skirt made with thin flax cylinders dyed a pretty soft green. Bev uses both naturally coloured and dyed fibre to make her little baskets which she exhibits widely and has won a number of awards for. Karl Leonard is an experienced skirt, or piupiu, maker and well used to preparing flax strips for these garments. Using a long ruler marked at different lengths as a guide, he cuts the flax halfway through on the back of the strips at each guide mark. Next he separates the green flesh of the leaf from the fibre in between the cut parts on the leaf. Karl advises that when preparing strips for patterning in this way, it’s important to keep the leaves damp as the fleshy part strips off much easier when the leaves are moist. To complete the preparation for piupiu making, the strips are boiled and hung up to dry where they curl into cylinders. The strips are then ready to be braided onto the waistband and dyed. When flax prepared in this way is dyed, the dye adheres to the fibre and not to the unscraped flax, making dyed and undyed blocks on the cylindrical strips which create the pattern.

Karl Leonard is an experienced skirt, or piupiu, maker and well used to preparing flax strips for these garments. Using a long ruler marked at different lengths as a guide, he cuts the flax halfway through on the back of the strips at each guide mark. Next he separates the green flesh of the leaf from the fibre in between the cut parts on the leaf. Karl advises that when preparing strips for patterning in this way, it’s important to keep the leaves damp as the fleshy part strips off much easier when the leaves are moist. To complete the preparation for piupiu making, the strips are boiled and hung up to dry where they curl into cylinders. The strips are then ready to be braided onto the waistband and dyed. When flax prepared in this way is dyed, the dye adheres to the fibre and not to the unscraped flax, making dyed and undyed blocks on the cylindrical strips which create the pattern. It was good to meet Felicity Champion at the gathering as we have corresponded over the years and Felicity has promoted my book to her weaving students. Felicity brought along a basket that she had woven using two different greens to make the pattern. Using colour in this way is very attractive and results in a subtle, natural blend of colours that I find very pleasing to the eye. Felicity’s basket caught many people’s admiring attention as they passed by.

It was good to meet Felicity Champion at the gathering as we have corresponded over the years and Felicity has promoted my book to her weaving students. Felicity brought along a basket that she had woven using two different greens to make the pattern. Using colour in this way is very attractive and results in a subtle, natural blend of colours that I find very pleasing to the eye. Felicity’s basket caught many people’s admiring attention as they passed by. Marie Flavell’s choice of weaving was a circular piece which she started and completed over the weekend. She started with a plait, adding in a number of red, black and natural coloured strips in a particular sequence and, as she wove, a pleasing flower-like pattern emerged. To make a circular piece like this, add the strips to the plait two or four at a time, overlapping them as they are added. This allows for the weaving to be curled around. Marie mentioned that her favourite weaving flax is

Marie Flavell’s choice of weaving was a circular piece which she started and completed over the weekend. She started with a plait, adding in a number of red, black and natural coloured strips in a particular sequence and, as she wove, a pleasing flower-like pattern emerged. To make a circular piece like this, add the strips to the plait two or four at a time, overlapping them as they are added. This allows for the weaving to be curled around. Marie mentioned that her favourite weaving flax is  Chris Bradshaw from Matata, a guest of honour at the gathering, has specialised in weaving hats, or pōtae and it was interesting to see the different style of hat that Chris wore each day. The hat pictured here is started at the crown using a method that is often seen for the start of the base of a container with pointed feet, in weaving from Asia. Another of Chris’s hats was woven with pīngao leaves, the fluted ends of the pīngao leaf, where it is pulled from the plant, being used as a decorative feature at the edge of the brim. I enjoyed seeing the variety of hats that Chris had woven and plan to make a hat for myself over the Christmas break.

Chris Bradshaw from Matata, a guest of honour at the gathering, has specialised in weaving hats, or pōtae and it was interesting to see the different style of hat that Chris wore each day. The hat pictured here is started at the crown using a method that is often seen for the start of the base of a container with pointed feet, in weaving from Asia. Another of Chris’s hats was woven with pīngao leaves, the fluted ends of the pīngao leaf, where it is pulled from the plant, being used as a decorative feature at the edge of the brim. I enjoyed seeing the variety of hats that Chris had woven and plan to make a hat for myself over the Christmas break. Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa, the Māori weavers’ association of New Zealand, hosted a national gathering, or hui, recently at Kawerau as part of their Biennial General Meeting. A number of participants wore woven cloaks to the customary welcome ceremony, or pōwhiri, which took place at the start of the gathering. Most of the cloaks shown here were woven in a traditional style, incorporating different coloured blocks or bands of feathers into the design. The striking red and black cloak was woven with the Tāniko method of twining coloured threads of flax fibre together in geometric patterns.

Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa, the Māori weavers’ association of New Zealand, hosted a national gathering, or hui, recently at Kawerau as part of their Biennial General Meeting. A number of participants wore woven cloaks to the customary welcome ceremony, or pōwhiri, which took place at the start of the gathering. Most of the cloaks shown here were woven in a traditional style, incorporating different coloured blocks or bands of feathers into the design. The striking red and black cloak was woven with the Tāniko method of twining coloured threads of flax fibre together in geometric patterns. Approximately two hundred weavers from throughout New Zealand participated and, as this was the first national weaving gathering I’d been to, I was very interested to see all the diversity and originality of the work people were doing. Cloaks, different types of baskets, mats, hats, flowers, containers, skirts, bottle covers, tiny decorative kete, hair pieces and more were in the process of construction. No formal workshops were held at the gathering but weavers shared ideas and techniques and learned from each other.

Approximately two hundred weavers from throughout New Zealand participated and, as this was the first national weaving gathering I’d been to, I was very interested to see all the diversity and originality of the work people were doing. Cloaks, different types of baskets, mats, hats, flowers, containers, skirts, bottle covers, tiny decorative kete, hair pieces and more were in the process of construction. No formal workshops were held at the gathering but weavers shared ideas and techniques and learned from each other. One of the highlights of the weekend was the Wearable Arts Fashion Show, which offered weavers an opportunity to showcase their own creations. Many of the people I talked to were formally studying Māori arts at tertiary institutions and a number were exhibiting in the show alongside more experienced weavers.

One of the highlights of the weekend was the Wearable Arts Fashion Show, which offered weavers an opportunity to showcase their own creations. Many of the people I talked to were formally studying Māori arts at tertiary institutions and a number were exhibiting in the show alongside more experienced weavers. The students, ranging across all ages, wove some innovative entries, including several wacky hats, for the fashion show. One particularly unusual hat was woven right around the model’s head so it’s no wonder the show was a bit late starting!

The students, ranging across all ages, wove some innovative entries, including several wacky hats, for the fashion show. One particularly unusual hat was woven right around the model’s head so it’s no wonder the show was a bit late starting! One group was using pīngao, a native golden sand sedge, which they had ready access to from the northern beaches near their home. (Pīngao is not readily available on southern beaches). In particular, adding feathers into garments, from birds such as rooster, pukeko and pheasant, was a popular theme. The sources of feathers include plucking feathers from road-kill birds, collecting feathers from bird-keepers, buying exotic feathers online, or buying them in packets from local craft suppliers.

One group was using pīngao, a native golden sand sedge, which they had ready access to from the northern beaches near their home. (Pīngao is not readily available on southern beaches). In particular, adding feathers into garments, from birds such as rooster, pukeko and pheasant, was a popular theme. The sources of feathers include plucking feathers from road-kill birds, collecting feathers from bird-keepers, buying exotic feathers online, or buying them in packets from local craft suppliers. The host group supplied flax for visitors and I used this to weave a small basket to hold the weaving tools I’d taken but didn’t have a container for. I made the basket with 36 strips of flax .75 cm wide, and gave it four corners to provide enough space for the tools.

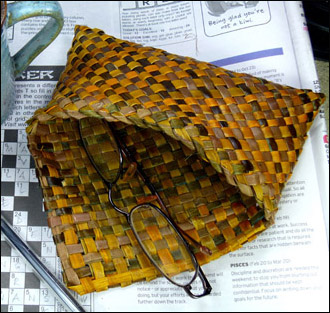

The host group supplied flax for visitors and I used this to weave a small basket to hold the weaving tools I’d taken but didn’t have a container for. I made the basket with 36 strips of flax .75 cm wide, and gave it four corners to provide enough space for the tools.  The flap tucks in to keep the tools in place, and is flexible enough to fold out so that the tools can be removed. At 20 cm long by 5 cm wide, it’s compact enough to fit into a small space in airline luggage.

The flap tucks in to keep the tools in place, and is flexible enough to fold out so that the tools can be removed. At 20 cm long by 5 cm wide, it’s compact enough to fit into a small space in airline luggage. While preparing a third edition of my book, Weaving Flowers from New Zealand Flax, I experimented with making flowers from netted flax, and the new edition now includes several netted-flax designs. Making netted flax with a pasta machine was discovered by Christall Rata and she gained a patent #336288 in 10 Jun 2002. Sema Morris from Artiflax later acquired patent and it lapsed on 15 Sep 2013, expiring on 15 Sep 2020. A variety of differently processed netted leaves and bouquets including netted flax are for sale from

While preparing a third edition of my book, Weaving Flowers from New Zealand Flax, I experimented with making flowers from netted flax, and the new edition now includes several netted-flax designs. Making netted flax with a pasta machine was discovered by Christall Rata and she gained a patent #336288 in 10 Jun 2002. Sema Morris from Artiflax later acquired patent and it lapsed on 15 Sep 2013, expiring on 15 Sep 2020. A variety of differently processed netted leaves and bouquets including netted flax are for sale from  It’s fun experimenting with netted flax because it can be manipulated in a wide variety of ways to make a range of delicate flowers which are quite different from flowers woven with un-netted flax. The Iris, Daisy and Tulips pictured here are all made from dyed netted flax. The Iris is simple to make and takes just a matter of minutes once the flax has been dyed, and the result is almost instantaneously rewarding. There are several different ways that the Iris can be shaped, and there are also different ways that the Daisy can be made. The version shown here combines a flower woven from un-netted flax — which I call a Tropical Rose in my book — with netted flax, which changes the look of the Tropical Rose completely. The Daisy can also be made without an un-netted flax flower in its centre, and more layers of netted petals can be added, opening up creative possibilities.

It’s fun experimenting with netted flax because it can be manipulated in a wide variety of ways to make a range of delicate flowers which are quite different from flowers woven with un-netted flax. The Iris, Daisy and Tulips pictured here are all made from dyed netted flax. The Iris is simple to make and takes just a matter of minutes once the flax has been dyed, and the result is almost instantaneously rewarding. There are several different ways that the Iris can be shaped, and there are also different ways that the Daisy can be made. The version shown here combines a flower woven from un-netted flax — which I call a Tropical Rose in my book — with netted flax, which changes the look of the Tropical Rose completely. The Daisy can also be made without an un-netted flax flower in its centre, and more layers of netted petals can be added, opening up creative possibilities. The Tulip is more structured and takes more time to make but I think the results are worth the effort. As well as including instructions for weaving netted-flax flower designs, the third edition of Weaving Flowers from New Zealand Flax includes a new section on flower arrangements for weddings and events. The book is now printed double sided on 100 gram paper, which is more robust. All the information about buying the book directly from me is on the

The Tulip is more structured and takes more time to make but I think the results are worth the effort. As well as including instructions for weaving netted-flax flower designs, the third edition of Weaving Flowers from New Zealand Flax includes a new section on flower arrangements for weddings and events. The book is now printed double sided on 100 gram paper, which is more robust. All the information about buying the book directly from me is on the