On this page

The history of flax use

The history of the word “flax”

The history of flax use

A full raincape made with shredded flax tags

Taniko border on the bottom of a Korowai cloak

Outer Kiwi feathers and woven base of a Kiwi feather cloak

A full skirt with a simple geometric pattern and taniko top border

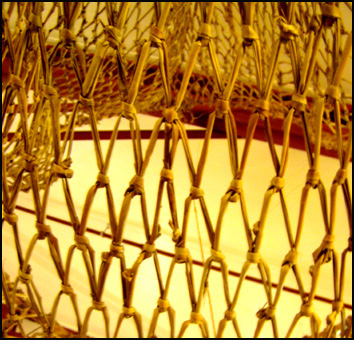

Fishing nets made by knotting strips of flax together

Woven flax sandals with plaited cords for tying

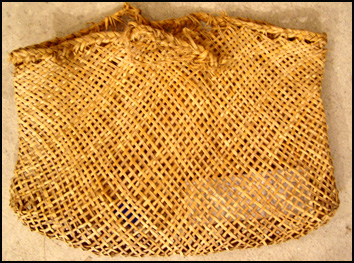

Open-weave work basket woven with fine strips

War belt for carrying weapons

For hundreds of years before the arrival of European settlers, Māori — the indigenous people of New Zealand — utilised native New Zealand flax as a raw material for clothing, food gathering, hunting, fishing, homeware and medicine. Māori communities cultivated plantations, or pa harakeke, of the flax varieties that had the best leaf and fibre qualities for their needs.

Flax was the primary material used in all types of clothing — rain capes, cloaks, skirts, loin cloths, sandals and belts. Rain capes used twined flax fibre for the base of the garment and short strips of the leaf to make a layered thatch on the outside. This shed the rain in much the same way as the thatch on an English cottage.

Flax cloaks ranged from the purely functional to the highly decorative. One style of cloak used the fibre from a special variety of flax, woven very evenly and finely, to make a soft draping garment with a silky sheen. These cloaks often had a Taniko border of dyed flax fibre woven in geometric patterns. Some cloaks had feathers entwined in the rows of flax. One highly prized style used feathers from the Kiwi, a flightless native bird that is now protected as the national symbol of New Zealand. The arrival of European goods in the mid-eighteenth century saw the introduction of pre-made cords, unravelled from woollen garments, as a popular decorative feature.

In the early twentieth century, flax skirts and loin cloths were constructed by hanging long strips of curled flax from a patterned waistband. The strips were prepared by exposing and dyeing small sections of the inner fibre of the leaf at measured intervals along the length of the strips. They were then left to dry and curl into long thin cylinders. When hung from the waistband, the dyed fibre sections made geometric patterns on the skirts and gave the cylinders the flexibility to flow gracefully with the movement of the wearer.

The strength and relative durability of flax made it ideal for sandals, fishing nets, sails, bird snares, ropes, floor mats and basketry. On long trips men took several pairs of sandals with them, weaving more as they wore out. Deep-sea fishing nets of up to 1000 metres in length were constructed entirely from flax strips, using the same type of knots as European net makers. Flax rope was used for building houses and boats, to fix stone heads to implements and for making bird snares. Flax mats were woven to cover the floors of buildings, and decorative wall coverings were made from dyed flax woven into patterns over a frame. The soft inner fibres of flax were used for babies’ mattresses.

Māori utilised a variety of different flax baskets in their daily tasks. For example, quickly-made baskets were used once for serving food and then thrown away. Shellfish were gathered in baskets with an open weave so that sand could be washed from the shellfish once they were gathered. Larger, open-weave baskets were used for gathering and storing potatoes. A harness of woven straps tied onto a person’s back was used to carry loads. (Modern backpacks are made in a different style and often use patterns and colours).

Flax was also valued by Māori for its medicinal properties. The leaves, gum, rhizomes and stalks of the flax plant were made into poultices, purgatives, disinfectants and ointments for skin disorders and wounds, stomach upsets and swollen joints.

In the mid-nineteenth century, flax began to be harvested by European settlers and exported to Australian and English rope manufacturers. Later, with the invention of the flax stripping machine, large-scale commercial processing became possible in New Zealand. Flax rope-making was a major industry for almost a century, with hundreds of flax mills operating during the boom years. During the depression in the 1930s the industry diversified into flax woolpacks but the advent of cheaper synthetic fibres in the 1970s spelt the end of the flax milling industry.

Flax weaving by hand almost died out as Māori became urbanised in the early part of the twentieth century, but there was a resurgence of interest in traditional flax crafts in the latter part of the century. Flax weaving is now an integral part of the cultural identity of New Zealand. Flax clothing is worn at cultural events, heirloom cloaks are worn for ceremonial occasions, and contemporary artists and craftspeople are increasingly using flax and flax products in their creations.

More recently there has also been a resurgence of interest in exploring the commercial potential of flax. Since the turn of century all parts of the New Zealand flax plant — fibre, seeds and gel — have begun to be researched for their potential value in fabrics, food oils, pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, and as a replacement for fibreglass.

New Zealand flax bush

Linum usitatissimum — linen flax plant

Pandanus-tectorius — Pandanus tree

Ti kouka — cabbage tree

Black NZ flax seeds and cream linen flax seeds, or linseeds

A roll of prepared pandanus

Bags from South East Asia made with reeds

Flax is the most well-known of the traditional weaving materials used in New Zealand. There can be confusion as to which material is used in a woven item and several entirely different plant species can be commonly referred to as flax:

1. Native New Zealand flax, Phormium tenax and Phormium cookianum, known by Māori as harakeke and wharariki, which is now cultivated in Europe and North America as a decorative plant.

2. Linen flax, Linum usitatissimum, which is farmed for fibre, seeds and linseed oil throughout the world, including New Zealand.

3. Pandanus, a genus of 600+ species, found in Australia and the Pacific Islands, but not in New Zealand.

4. A wide variety of other plants with leaves or bark that can usefully be woven as flat strips, found in New Zealand and elsewhere.

The use of the same word for different species often causes considerable confusion. For example, the flax seed sold in health food shops is sometimes thought to come from New Zealand flax, but invariably comes from linen flax, imported or grown in New Zealand. Also, people sometimes get the impression that the flax mats and baskets sold by New Zealand retailers are woven from New Zealand flax, but in many cases they have been imported from the South Pacific or South-East Asia and are woven from pandanus, reeds or other plants.

So how did this confusion over the word “flax” arise? It’s perhaps not surprising that the first European settlers referred to harakeke as New Zealand flax when they saw the finely woven garments that Māori made from harakeke, which so closely resembled the garments woven from linen flax in Europe.

Although the fibre of linen flax and New Zealand flax is similar, the plants are very different. Linen flax is a fine-leaved shrub and its fibre is taken from its stems, whereas New Zealand flax grows long, tough leaves from the base of the plant, and its leaves can be peeled for fibre or cut into strips.

Pandanus is somewhere between a shrub and a tree, with leaves that are similar to New Zealand flax, though generally smaller, softer and less fibrous. The process of preparing strips of pandanus for weaving is more complicated than that of preparing strips of New Zealand flax, but the weaving process itself is similar for both.

Māori are thought to have brought Pandanus seeds to New Zealand when they first arrived from the Pacific Islands, some 1,000 years ago. However, Pandanus never really took to the New Zealand environment, and it wouldn’t have taken long for Māori to appreciate the suitability of the New Zealand flax plant, both as a source of strips with which to weave baskets and as a soft fibre with which to weave fine flowing garments.

Although New Zealand flax was the main source of weaving material for Māori, they also used the leaves or bark of other native New Zealand plants — ti kauka or ti rakau (Cordyline australis, the New Zealand cabbage tree), hoheria (Hoheria sexstylosa, the New Zealand lacebark), kiekie (Freycinetia banksii, a climbing plant), kuta (Eleocharis sphacelata, a tall reed), pingao (Desmoschoenus spiralis, a coastal sedge grass), and toetoe (Cortaderia toetoe, a large grass). For examples of Māori baskets or ketes made from these materials, go to the Auckland Museum website. A search for ‘Weaving’ takes you to a number of links to weaving in their collections.

Naturally, there is a strong similarity between the style of the mats and baskets that Māori wove in New Zealand and the mats and baskets woven in the Pacific Islands — they are both offshoots from the same tradition. The weaving technique itself appears to have been independently developed by indigenous people all over the world.

It seems that the word “flax” is nearly as well travelled as the basic techniques for weaving it. In New Zealand, when the word “flax” is associated with weaving, it generally refers to weaving made from the New Zealand flax plant, but weaving from the leaves of other native New Zealand plants can also be referred to as flax weaving. In some islands in the South Pacific, the word “flax” refers to Pandanus, and in others it refers to linen flax.

For further information on the botanical characteristics of New Zealand flax, linen flax and pandanus, see the Wikipedia entries on New Zealand flax, flax and pandanus.

Thanks go to the Director of the Okains Bay Māori and Colonial Museum for permission to photograph items in the museum collection, to Functional Whole Foods New Zealand Ltd for the image of the linen flax plants, and to Wikipedia for the images of the Pandanus tree and the

New Zealand cabbage tree.

© Ali Brown 2006. Last updated 2021