17 December 2009

The flaxen-haired angel in the photo is a variation on the flax angel I posted instructions for at this time last year. This angel is a bit more fiddly and long-winded to make but I think the extra effort is worth it. I dyed her hair with yellow dye to give her golden locks but it’s not essential to do the dying if you don’t have access to yellow dye. Her halo is another addition this year and her wings have been shaped to make them more feathery. I hope you enjoy making her.

The flaxen-haired angel in the photo is a variation on the flax angel I posted instructions for at this time last year. This angel is a bit more fiddly and long-winded to make but I think the extra effort is worth it. I dyed her hair with yellow dye to give her golden locks but it’s not essential to do the dying if you don’t have access to yellow dye. Her halo is another addition this year and her wings have been shaped to make them more feathery. I hope you enjoy making her.

Start making the angel by shredding some flax with an animal comb or fork and tying a bundle of it with a strip of flax. Tie it with a double knot quite near the narrow ends of the shreds. Pull some of the waste flax out of the comb you have used to shred the flax with, and roll it into a small ball.

Start making the angel by shredding some flax with an animal comb or fork and tying a bundle of it with a strip of flax. Tie it with a double knot quite near the narrow ends of the shreds. Pull some of the waste flax out of the comb you have used to shred the flax with, and roll it into a small ball.

Position the flax ball into the middle of the shredded flax just above where it has been tied.

Position the flax ball into the middle of the shredded flax just above where it has been tied.

This is going to give some shape to the head. It’s quite tricky to keep this flax ball in place so you may find it’s a good idea to put some glue at several points around the circumference of the ball to hold the shredded flax in place as you continue to make the angel.

This is going to give some shape to the head. It’s quite tricky to keep this flax ball in place so you may find it’s a good idea to put some glue at several points around the circumference of the ball to hold the shredded flax in place as you continue to make the angel.

Tie another strip of flax at the top of the flax ball making sure that the flax shreds completely surround the flax ball.

Tie another strip of flax at the top of the flax ball making sure that the flax shreds completely surround the flax ball.

At this point I dipped the long thin ends of the shreds, up to the top tie, into boiling yellow dye, as I wanted the angel to have golden curls, but this is not an essential step. I used Teri Golden Yellow dye, and, as I used a flax with quite a lot of white in the colouring, it only needed a brief dip in the dye.

At this point I dipped the long thin ends of the shreds, up to the top tie, into boiling yellow dye, as I wanted the angel to have golden curls, but this is not an essential step. I used Teri Golden Yellow dye, and, as I used a flax with quite a lot of white in the colouring, it only needed a brief dip in the dye.

Now plait the long thin ends that come out of the top of the head into long braids. Separate the fibres carefully and make sure you are using fibres that come from the same area of the head for each braid.

Now plait the long thin ends that come out of the top of the head into long braids. Separate the fibres carefully and make sure you are using fibres that come from the same area of the head for each braid.

Shred a little bit more flax for the arms. Tie the shreds together in the middle to make a bundle and then slip this in between the shredded flax of the body. Push it up so that it’s right underneath the tie for the neck. Tie another piece of flax around the body below the arms to create a waist.

Shred a little bit more flax for the arms. Tie the shreds together in the middle to make a bundle and then slip this in between the shredded flax of the body. Push it up so that it’s right underneath the tie for the neck. Tie another piece of flax around the body below the arms to create a waist.

Now shred some more flax and divide it into two bundles. Drape one bundle over the right shoulder and bring it across the front of the body to the left. Drape the second bundle over the left shoulder and bring it across in front of the body to the right. Tie these in place around the waist with a wide strip of flax.

Now shred some more flax and divide it into two bundles. Drape one bundle over the right shoulder and bring it across the front of the body to the left. Drape the second bundle over the left shoulder and bring it across in front of the body to the right. Tie these in place around the waist with a wide strip of flax.

Bend the arms around to the front, tie a thin strip of flax around the flax at the right distance to make wrists for the arms and then cut off the ends of the flax, and shaping the ends into hands. Hold the hands together temporarily with a tie of flax so that as the flax dries, that arms stay in the bended shape.

Bend the arms around to the front, tie a thin strip of flax around the flax at the right distance to make wrists for the arms and then cut off the ends of the flax, and shaping the ends into hands. Hold the hands together temporarily with a tie of flax so that as the flax dries, that arms stay in the bended shape.

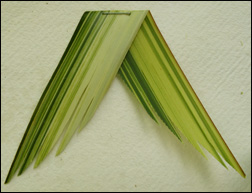

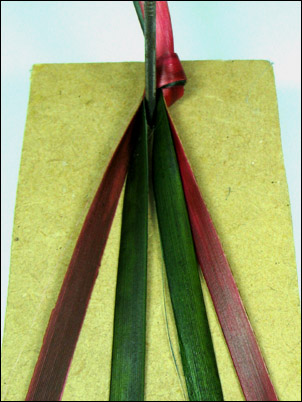

Now make the wings. I’ve used a thin, soft variegated flax for the illustration here but the thinner flax tends to curl up too much as it dries so I suggest you use a thicker flax for this style of wings. Take a piece of a flax leaf and scrape a blunt knife along both sides to soften and dry it a little to prevent the wings from curling up. Fold the flax on an angle with the fold at the top and a piece of flax coming down at an angle on each side and cut these sides into wing shapes. Staple the pieces in place close to the fold. Split each wing into about five strips just a bit over halfway along the wing. Use fine scissors to round the end of each strip and then cut up the strip a bit to narrow it and to give a feathery effect.

Now make the wings. I’ve used a thin, soft variegated flax for the illustration here but the thinner flax tends to curl up too much as it dries so I suggest you use a thicker flax for this style of wings. Take a piece of a flax leaf and scrape a blunt knife along both sides to soften and dry it a little to prevent the wings from curling up. Fold the flax on an angle with the fold at the top and a piece of flax coming down at an angle on each side and cut these sides into wing shapes. Staple the pieces in place close to the fold. Split each wing into about five strips just a bit over halfway along the wing. Use fine scissors to round the end of each strip and then cut up the strip a bit to narrow it and to give a feathery effect.

Position the wings just at shoulder height on the angel and attach them with glue or double-sided tape or a staple. I used double-sided tape which I find holds the wings securely.

Position the wings just at shoulder height on the angel and attach them with glue or double-sided tape or a staple. I used double-sided tape which I find holds the wings securely.

It’s now time to unplait the braids and let the angel’s hair down! Or you could leave the braids in place, for a more funky look for the angel. If you do this, I suggest you plait some more braids separately and then sew them onto the angel’s head as they could be a bit sparse otherwise.

It’s now time to unplait the braids and let the angel’s hair down! Or you could leave the braids in place, for a more funky look for the angel. If you do this, I suggest you plait some more braids separately and then sew them onto the angel’s head as they could be a bit sparse otherwise.

To make the angel’s halo, take a thin strip of flax, about .5 cm wide and as long as you can get it without using the tough bit of the leaf. Soften it with a knife and then fold it at right angles in the middle of the strip. It’s easiest to do this on a flat surface to start with.

To make the angel’s halo, take a thin strip of flax, about .5 cm wide and as long as you can get it without using the tough bit of the leaf. Soften it with a knife and then fold it at right angles in the middle of the strip. It’s easiest to do this on a flat surface to start with.

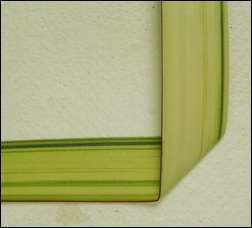

Take the end of the strip that is out to the left and fold it across to the right over the first fold.

Take the end of the strip that is out to the left and fold it across to the right over the first fold.

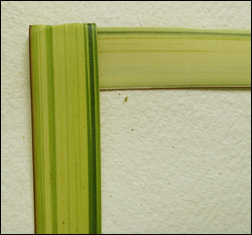

Take the end of the strip that is pointing up to the top and fold it down over the strip pointing to the left, folding it neatly against the other strip.

Take the end of the strip that is pointing up to the top and fold it down over the strip pointing to the left, folding it neatly against the other strip.

Continue to fold the strips over each other like this, until you have used up all the length of the strip. Make sure you fold the each strip squarely and closely up against the last strip otherwise the halo will be a bit loose, which may not be appropriate for an angel!

Continue to fold the strips over each other like this, until you have used up all the length of the strip. Make sure you fold the each strip squarely and closely up against the last strip otherwise the halo will be a bit loose, which may not be appropriate for an angel!

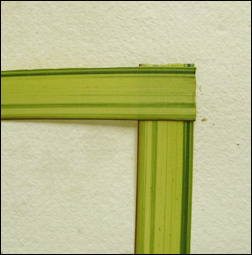

Hold the ends closely so that the folded strips don’t come undone and then curl the strip into a circle. Attach the ends together so that the halo is the right size for the angel’s head.

Hold the ends closely so that the folded strips don’t come undone and then curl the strip into a circle. Attach the ends together so that the halo is the right size for the angel’s head.

Attach the halo to the back of the angel’s head with glue or double-sided tape. Trim the long hair and arrange it so that it sits prettily around the angel’s shoulders and your angel is completed.

Attach the halo to the back of the angel’s head with glue or double-sided tape. Trim the long hair and arrange it so that it sits prettily around the angel’s shoulders and your angel is completed.

I recently received a letter from Kathy of Takaka who writes “We had an excellent hui with the local primary school (40 kids) who loved making your angel. They all went home clutching their one, along with a poi and kowhaiwhai pattern they had coloured in. A happy and successful first visit to our marae for a lot of them.” It’s lovely to hear that people have enjoyed making the original angel and I hope you enjoy making this version. Do send me a photo if you have your own variations.

© Ali Brown 2009.

Scroll down to leave a new comment or view recent comments.

Also, check out earlier comments received on this blog post when it was hosted on my original website.

Do you meet in a flax weaving group that is open to new participants or visitors? If so, do add a comment on this blog post with the group’s location, contact details and perhaps any other information you think might be of interest. If there are enough groups, I’ll create a Flax weaving groups section on the new

Do you meet in a flax weaving group that is open to new participants or visitors? If so, do add a comment on this blog post with the group’s location, contact details and perhaps any other information you think might be of interest. If there are enough groups, I’ll create a Flax weaving groups section on the new  It was fun googling for links, and I came across a number of examples of flax weaving online that I hadn’t seen before, like the wall hanging by Jess Parone, pictured on the right, and the sculpture by Jan van de Klundert, pictured below. In the last few years, I’ve noticed that more and more examples of flax weaving have been going online. There is always something new.

It was fun googling for links, and I came across a number of examples of flax weaving online that I hadn’t seen before, like the wall hanging by Jess Parone, pictured on the right, and the sculpture by Jan van de Klundert, pictured below. In the last few years, I’ve noticed that more and more examples of flax weaving have been going online. There is always something new. It’s good to see the increasing interest and exposure of flax weaving, and I’ve also been surprised and pleased by the number of people from other countries who have bought my book. It seems that New Zealand flax is spreading all over the world. Also, I don’t know whether it is the same in other cities, but more and more new houses in Christchurch seem to have flax plants in their front garden.

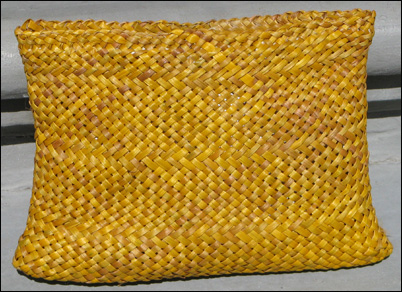

It’s good to see the increasing interest and exposure of flax weaving, and I’ve also been surprised and pleased by the number of people from other countries who have bought my book. It seems that New Zealand flax is spreading all over the world. Also, I don’t know whether it is the same in other cities, but more and more new houses in Christchurch seem to have flax plants in their front garden. A plant with the common name cutty grass — with its reputation for cutting fingers if they’re run along it — is an unlikely plant to use for weaving, especially as its short, narrow blades limit its use. However cutty grass, or pīngao, a native coastal plant, has one quality that, for weavers, surpasses its apparent shortcomings and that’s the deep golden yellow colour that it changes to once it’s dried. The beautiful little kete pictured here, woven by

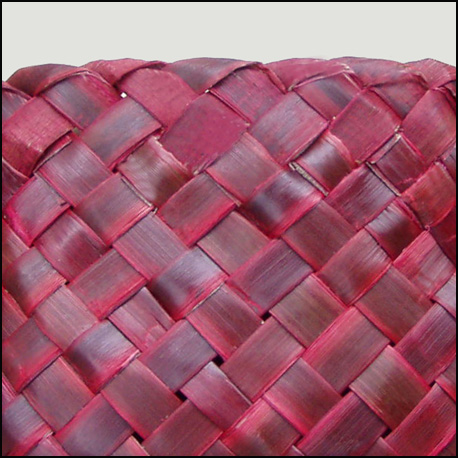

A plant with the common name cutty grass — with its reputation for cutting fingers if they’re run along it — is an unlikely plant to use for weaving, especially as its short, narrow blades limit its use. However cutty grass, or pīngao, a native coastal plant, has one quality that, for weavers, surpasses its apparent shortcomings and that’s the deep golden yellow colour that it changes to once it’s dried. The beautiful little kete pictured here, woven by  My interest in pīngao was sparked when one of the participants in a recent workshop brought some pīngao blades along to weave with. Karen, who bought the little Kohai Grace kete a couple of years ago, had been growing the pīngao for three or four years and it had reached the stage where the blades were long enough to use. The blades are mostly midrib with a small amount of soft leaf each side, and with one side narrower in width than the other. The blades are quite hard but soften very easily when a knife is run along them. Karen discovered very quickly that it was wise to have gloves on when softening the blades as it lived up to its name of cutty grass. She also found that she didn’t need to soften the pīngao as much as she normally would with flax and that the narrowest side of the blades tended to split off. She ended up removing this narrow side on all the blades although she may not have needed to if the softening hadn’t been quite as vigorous.

My interest in pīngao was sparked when one of the participants in a recent workshop brought some pīngao blades along to weave with. Karen, who bought the little Kohai Grace kete a couple of years ago, had been growing the pīngao for three or four years and it had reached the stage where the blades were long enough to use. The blades are mostly midrib with a small amount of soft leaf each side, and with one side narrower in width than the other. The blades are quite hard but soften very easily when a knife is run along them. Karen discovered very quickly that it was wise to have gloves on when softening the blades as it lived up to its name of cutty grass. She also found that she didn’t need to soften the pīngao as much as she normally would with flax and that the narrowest side of the blades tended to split off. She ended up removing this narrow side on all the blades although she may not have needed to if the softening hadn’t been quite as vigorous. Karen wanted to use the whole length of her pīngao blades and so wove a kete that was joined at the bottom, ending up with a kete about twelve cm high. She plaited around the top, continuing the plait with the remaining lengths until they were used up and then wound this thick plait around the top of the kete. As Karen wasn’t happy with her first attempts, the pīngao strips were worked quite a lot as she undid and rewove her work and the stress on the blades, where they’ve split and shredded, can be seen in the photo here. However, the final kete has its own character and uniqueness and is attractive as a whole.

Karen wanted to use the whole length of her pīngao blades and so wove a kete that was joined at the bottom, ending up with a kete about twelve cm high. She plaited around the top, continuing the plait with the remaining lengths until they were used up and then wound this thick plait around the top of the kete. As Karen wasn’t happy with her first attempts, the pīngao strips were worked quite a lot as she undid and rewove her work and the stress on the blades, where they’ve split and shredded, can be seen in the photo here. However, the final kete has its own character and uniqueness and is attractive as a whole. Although pīngao, a sand-binding plant, whose long trailing rhizomes help to stop erosion on sand dunes, once grew plentifully on coastal sand dunes throughout New Zealand, its growth declined rapidly as a consequence of burning and grazing by wild and domestic animals and overgrowth by marram grass. Harvesting methods have also contributed to this decline. Studies show that cutting a whole leaf cluster from the plant or wrenching the blades from the plant damages the growth. Clipping individual blades is now recommended as the most desirable harvesting method as it means only the useable blades are cut and that the plant is not damaged during the process.

Although pīngao, a sand-binding plant, whose long trailing rhizomes help to stop erosion on sand dunes, once grew plentifully on coastal sand dunes throughout New Zealand, its growth declined rapidly as a consequence of burning and grazing by wild and domestic animals and overgrowth by marram grass. Harvesting methods have also contributed to this decline. Studies show that cutting a whole leaf cluster from the plant or wrenching the blades from the plant damages the growth. Clipping individual blades is now recommended as the most desirable harvesting method as it means only the useable blades are cut and that the plant is not damaged during the process. As I don’t have ready access to harvesting pīngao, and it seems to be relatively easy to grow, I decided to grow some pīngao plants in my garden. I bought six plants, grown from seed sourced from

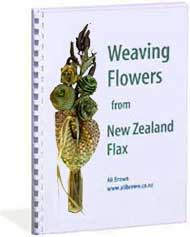

As I don’t have ready access to harvesting pīngao, and it seems to be relatively easy to grow, I decided to grow some pīngao plants in my garden. I bought six plants, grown from seed sourced from  The book I’ve been writing, Weaving Flowers from New Zealand Flax, is now ready for sale. It contains detailed instructions for weaving fifteen different flower and foliage designs as well as different variations of several of the designs. The book also includes examples of flower arrangements for the designs, and additional flax foliage ideas for flower arrangements. Most of the flower designs can be woven from a single flax leaf, and are very quick to weave once you’ve had a bit of practice — many of them are much quicker to weave than the flower design shown on the Weaving a flax flower page in the Instructions section of this website.

The book I’ve been writing, Weaving Flowers from New Zealand Flax, is now ready for sale. It contains detailed instructions for weaving fifteen different flower and foliage designs as well as different variations of several of the designs. The book also includes examples of flower arrangements for the designs, and additional flax foliage ideas for flower arrangements. Most of the flower designs can be woven from a single flax leaf, and are very quick to weave once you’ve had a bit of practice — many of them are much quicker to weave than the flower design shown on the Weaving a flax flower page in the Instructions section of this website. Flowers woven from flax have become very popular over the last couple of years or so. Bunches of woven flax flowers are now offered for sale on TradeMe, and on the websites

Flowers woven from flax have become very popular over the last couple of years or so. Bunches of woven flax flowers are now offered for sale on TradeMe, and on the websites  Woven flowers also make great projects for a beginner in flax weaving, and one of the advantages of flax flowers is that any variety of New Zealand flax can be used to weave them, including the coloured, variegated flaxes that are often grown as decorative garden plants throughout the world. Most of the instructions in the book are illustrated with the coloured flaxes, and show how nice they look as woven flowers. Of course, New Zealand flax is not essential for weaving flowers. As I mention on my

Woven flowers also make great projects for a beginner in flax weaving, and one of the advantages of flax flowers is that any variety of New Zealand flax can be used to weave them, including the coloured, variegated flaxes that are often grown as decorative garden plants throughout the world. Most of the instructions in the book are illustrated with the coloured flaxes, and show how nice they look as woven flowers. Of course, New Zealand flax is not essential for weaving flowers. As I mention on my  Although most of the designs in the book are made from a single flax leaf, a few designs or variations are rather more elaborate, and one or two — like the sunflower shown on the right — require many leaves. Other photos from the book are shown in my

Although most of the designs in the book are made from a single flax leaf, a few designs or variations are rather more elaborate, and one or two — like the sunflower shown on the right — require many leaves. Other photos from the book are shown in my  At the same time that I’m putting up this blog post, I’m also emailing all the people who have asked to be notified when the book came out, including some people who bought an earlier booklet that I put together rather quickly in 2007 when I was invited to

At the same time that I’m putting up this blog post, I’m also emailing all the people who have asked to be notified when the book came out, including some people who bought an earlier booklet that I put together rather quickly in 2007 when I was invited to  Incidentally, the price of the book is considerably higher than the earlier booklet. This reflects the increase in size, from a 16-page booklet of 5 flower designs with small photographs to a 115-page book of 12 flower designs and 3 foliage designs with much larger photographs and more detailed instructions, as well as flower arrangements and additional flax foliage ideas.

Incidentally, the price of the book is considerably higher than the earlier booklet. This reflects the increase in size, from a 16-page booklet of 5 flower designs with small photographs to a 115-page book of 12 flower designs and 3 foliage designs with much larger photographs and more detailed instructions, as well as flower arrangements and additional flax foliage ideas. I imagine those who purchased the earlier booklet will find the book greatly improved. As well as the increase in size and detail, the quality of the photographs, instructions and layout is also much improved. However, I’ve no doubt that the book can be improved still further. If you

I imagine those who purchased the earlier booklet will find the book greatly improved. As well as the increase in size and detail, the quality of the photographs, instructions and layout is also much improved. However, I’ve no doubt that the book can be improved still further. If you  Even though there are only a few days to go before Christmas, there’s still time to make the odd flax decoration. Shredded flax lends itself to making an angel in much the same way that straw and grasses have traditionally been used to make angels in other cultures, and it is a very quick and easy design to construct. I’ve used variegated flax for the angel design illustrated in these instructions, which gives the wings a textured look, although any flax that not too strong or thick is suitable.

Even though there are only a few days to go before Christmas, there’s still time to make the odd flax decoration. Shredded flax lends itself to making an angel in much the same way that straw and grasses have traditionally been used to make angels in other cultures, and it is a very quick and easy design to construct. I’ve used variegated flax for the angel design illustrated in these instructions, which gives the wings a textured look, although any flax that not too strong or thick is suitable. Shred two or three flax leaves with a fork or dog comb. Tie the shredded flax into a bundle with another piece of flax.

Shred two or three flax leaves with a fork or dog comb. Tie the shredded flax into a bundle with another piece of flax. Turn the bundle up the other way so that the tie is inside the bundle and the shredded flax hangs down and around the tie, then tie another strip of flax around the bundle. This will make the neck of the angel.

Turn the bundle up the other way so that the tie is inside the bundle and the shredded flax hangs down and around the tie, then tie another strip of flax around the bundle. This will make the neck of the angel. Shred a little bit more flax for the arms. Tie the shredded flax together in the middle and then slip it in between the shredded flax of the body. Push it up so that it’s right underneath the tie for the neck.

Shred a little bit more flax for the arms. Tie the shredded flax together in the middle and then slip it in between the shredded flax of the body. Push it up so that it’s right underneath the tie for the neck. Tie another piece of flax around the body below the arms to create a waist. Now shred some more flax and divide it into two bundles.

Tie another piece of flax around the body below the arms to create a waist. Now shred some more flax and divide it into two bundles.

Drape one bundle over the right shoulder and bring it across the front of the body to the left. Drape the second bundle over the left shoulder and bring it across in front of the body to the right. Tie these in place around the waist.

Drape one bundle over the right shoulder and bring it across the front of the body to the left. Drape the second bundle over the left shoulder and bring it across in front of the body to the right. Tie these in place around the waist.

Bend the arms around to the front and tie them together in the front of the body. Cut off the ends of the flax, shaping the ends into hands.

Bend the arms around to the front and tie them together in the front of the body. Cut off the ends of the flax, shaping the ends into hands. To make very simple wings, take a piece of a flax leaf and scrape a blunt knife along both sides to soften and dry it a little to prevent the wings from curling up. Fold the flax on an angle with the fold at the top and a piece of flax coming down at an angle on each side and cut these sides into wing shapes. Staple the pieces in place close to the fold. (I used variegated flax to make the wings look feathery but no doubt more elaborate wings could be made by splitting and folding the flax in other ways). Attach the wings to the angel’s shoulders at the back. I stapled the wings on but you could use superglue.

To make very simple wings, take a piece of a flax leaf and scrape a blunt knife along both sides to soften and dry it a little to prevent the wings from curling up. Fold the flax on an angle with the fold at the top and a piece of flax coming down at an angle on each side and cut these sides into wing shapes. Staple the pieces in place close to the fold. (I used variegated flax to make the wings look feathery but no doubt more elaborate wings could be made by splitting and folding the flax in other ways). Attach the wings to the angel’s shoulders at the back. I stapled the wings on but you could use superglue. You can draw a face on the angel or use a shell for her face. I’ve left the face as it is but have given her a halo by placing a rounded, smoothed-by-the-sea piece of shell on the top of her head.

You can draw a face on the angel or use a shell for her face. I’ve left the face as it is but have given her a halo by placing a rounded, smoothed-by-the-sea piece of shell on the top of her head. The flax weaving techniques used in basket making are often the same techniques that other countries around the world use in their traditional weaving, although the raw materials are different. I always find it fascinating to see a sample of this universal nature of weaving, so I was most interested when one of my students showed me a three-dimensional star, made with birch bark, that she had purchased on her recent visit to the USA. The star is the same as the one shown on the blog post,

The flax weaving techniques used in basket making are often the same techniques that other countries around the world use in their traditional weaving, although the raw materials are different. I always find it fascinating to see a sample of this universal nature of weaving, so I was most interested when one of my students showed me a three-dimensional star, made with birch bark, that she had purchased on her recent visit to the USA. The star is the same as the one shown on the blog post,  To make this three-dimensional star, follow the steps for making the eight-pointed star on the

To make this three-dimensional star, follow the steps for making the eight-pointed star on the  Take the top strip of the two end-strips that are laying out to the right and bend it back on itself. The folded point underneath it is now showing.

Take the top strip of the two end-strips that are laying out to the right and bend it back on itself. The folded point underneath it is now showing. Take the right-hand strip of the two end-strips that are coming out from the bottom of the star, and fold it up to the top, exposing the folded point at the bottom right.

Take the right-hand strip of the two end-strips that are coming out from the bottom of the star, and fold it up to the top, exposing the folded point at the bottom right. Now fold it across to the right on a 45-degree angle. Keep the start of the fold as close to the centre of the star as possible. Press it down to crease it.

Now fold it across to the right on a 45-degree angle. Keep the start of the fold as close to the centre of the star as possible. Press it down to crease it. Bring the end of this strip back around and poke it underneath the first strip that was bent back on itself. Push the end right through so that it comes out between the middle of the folds of the top point on the left.

Bring the end of this strip back around and poke it underneath the first strip that was bent back on itself. Push the end right through so that it comes out between the middle of the folds of the top point on the left. Pull the strip through until it folds around into a spike. Don’t pull too far or it will undo the spike. Squeeze the strip to make it more spikey. Alternatively, to make the spike more open, push your finger into the centre of the spike and push the flax out to shape it.

Pull the strip through until it folds around into a spike. Don’t pull too far or it will undo the spike. Squeeze the strip to make it more spikey. Alternatively, to make the spike more open, push your finger into the centre of the spike and push the flax out to shape it. Repeat these steps for the other three strips on this side of the star. As this version has a flat side, it can be used to tie around gifts.

Repeat these steps for the other three strips on this side of the star. As this version has a flat side, it can be used to tie around gifts. For the second version of the star, make spikes on the other side in the same way as the first side. To finish, cut off all the ends. This side view shows the spikes poking out from both sides. To hang the star up, split a thin strip off the inner side of one end and cut the rest of the strip off.

For the second version of the star, make spikes on the other side in the same way as the first side. To finish, cut off all the ends. This side view shows the spikes poking out from both sides. To hang the star up, split a thin strip off the inner side of one end and cut the rest of the strip off. According to archaeologists, cords have been made by plaiting or twisting plant materials since about 17,000 BC, typically nettles, hemp, cotton, sisal and jute. In traditional Māori culture, cord has been made from New Zealand flax, which is probably at least as strong and durable as any other plant material. Before rope began to be made from plastics in the late twentieth century, its manufacture from flax fibre was one of New Zealand’s major export industries.

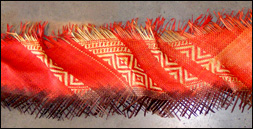

According to archaeologists, cords have been made by plaiting or twisting plant materials since about 17,000 BC, typically nettles, hemp, cotton, sisal and jute. In traditional Māori culture, cord has been made from New Zealand flax, which is probably at least as strong and durable as any other plant material. Before rope began to be made from plastics in the late twentieth century, its manufacture from flax fibre was one of New Zealand’s major export industries. Flax can be plaited from its fibre or from strips, and the photo to the right shows a four-plait made from flax fibre, or muka, on the left side of the photo and one from strips on the right side. A plait made from fibre is a good deal stronger than one made from strips, but plaited strips are much quicker to make and look quite attractive, particularly the four-plait, which can be woven in a tubular shape. A disadvantage of the tubular shape is that it can become crushed if used as a handle for a basket carrying heavy weights, but it’s quite suitable for a small basket and it’s particularly suitable for a pendant.

Flax can be plaited from its fibre or from strips, and the photo to the right shows a four-plait made from flax fibre, or muka, on the left side of the photo and one from strips on the right side. A plait made from fibre is a good deal stronger than one made from strips, but plaited strips are much quicker to make and look quite attractive, particularly the four-plait, which can be woven in a tubular shape. A disadvantage of the tubular shape is that it can become crushed if used as a handle for a basket carrying heavy weights, but it’s quite suitable for a small basket and it’s particularly suitable for a pendant. A four-plait cord made from strips becomes tubular because the shiny side of each strip is kept to the outside of the cord all the time as you plait. Start with four flax strips all the same width. As for any cord, it’s easier to get an even plait if you have one end of the work held by a friend or you tie the end around a solid object such as a chair leg or a nail in a piece of wood. This means you can pull the strands towards you as you plait, so you can keep an even tension on the plaiting. Here I’ve used a nail banged into a piece of wood. Arrange the strips so that the shiny side of each strip is showing uppermost.

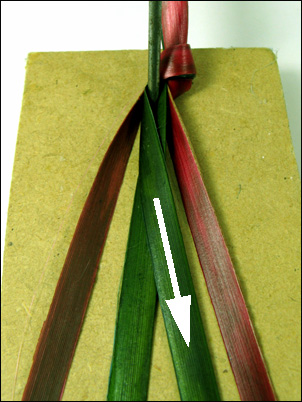

A four-plait cord made from strips becomes tubular because the shiny side of each strip is kept to the outside of the cord all the time as you plait. Start with four flax strips all the same width. As for any cord, it’s easier to get an even plait if you have one end of the work held by a friend or you tie the end around a solid object such as a chair leg or a nail in a piece of wood. This means you can pull the strands towards you as you plait, so you can keep an even tension on the plaiting. Here I’ve used a nail banged into a piece of wood. Arrange the strips so that the shiny side of each strip is showing uppermost. I’ve used two strips of dyed green flax and two strips of dyed red flax for these illustrations to show the plaiting sequence more easily. If you are using two different colours, arrange the colours so that one colour is used for the two outside strips and the second colour is used for the two inside strips. To start plaiting, grasp the middle two green strips, and cross the left-hand one over the right-hand one, keeping the shiny side uppermost.

I’ve used two strips of dyed green flax and two strips of dyed red flax for these illustrations to show the plaiting sequence more easily. If you are using two different colours, arrange the colours so that one colour is used for the two outside strips and the second colour is used for the two inside strips. To start plaiting, grasp the middle two green strips, and cross the left-hand one over the right-hand one, keeping the shiny side uppermost. Then take the outside left-hand red strip, and bring it under the two green strips to the right of it, turning it so the shiny side of the flax will be showing on the underneath of the cord. This means that the dull side of the strip is showing at the front. Bring this strip around and over one green strip next to it on the left. The shiny side of this strip should now be showing.

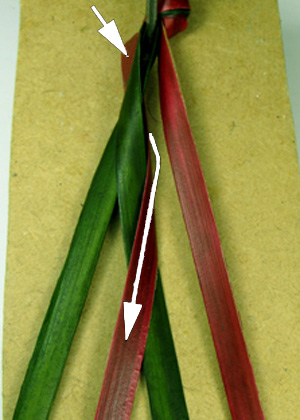

Then take the outside left-hand red strip, and bring it under the two green strips to the right of it, turning it so the shiny side of the flax will be showing on the underneath of the cord. This means that the dull side of the strip is showing at the front. Bring this strip around and over one green strip next to it on the left. The shiny side of this strip should now be showing. Go to the right hand side of the plait and take the outside red strip to the left under the next two strips, (one is red and one is green), keeping the shiny side of the flax on the outside of the cord so that the dull side shows on the front. Bring this strip around and over the one red strip to the right of it so that the shiny side of this strip is now showing. Note that the two green strips are now on the outside and the two red strips are in the middle.

Go to the right hand side of the plait and take the outside red strip to the left under the next two strips, (one is red and one is green), keeping the shiny side of the flax on the outside of the cord so that the dull side shows on the front. Bring this strip around and over the one red strip to the right of it so that the shiny side of this strip is now showing. Note that the two green strips are now on the outside and the two red strips are in the middle. To continue, go back to the left hand side and take the outside green strip under the two red strips and then turn it back over one red strip, making sure you keep the shiny side of the flax on the outside of the cord as you do this.

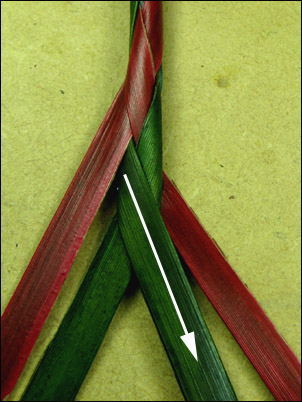

To continue, go back to the left hand side and take the outside green strip under the two red strips and then turn it back over one red strip, making sure you keep the shiny side of the flax on the outside of the cord as you do this.  Now go the right hand side and take the outside green strip under two strips, (one is green and one is red), and then turn it back over one green strip. Pull the strips out each side and up so that the plaiting tightens up and the tubular shape and pattern of the cord starts showing. Continue plaiting, pulling the plait up tightly and evenly as you go.

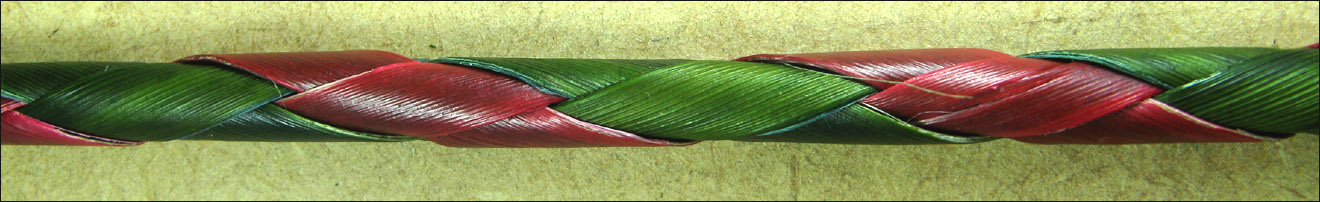

Now go the right hand side and take the outside green strip under two strips, (one is green and one is red), and then turn it back over one green strip. Pull the strips out each side and up so that the plaiting tightens up and the tubular shape and pattern of the cord starts showing. Continue plaiting, pulling the plait up tightly and evenly as you go. The nice thing about weaving a four-plait cord with two different colours is that the colours spiral around the cord, giving it a candy-stripe effect, which I find very attractive.

The nice thing about weaving a four-plait cord with two different colours is that the colours spiral around the cord, giving it a candy-stripe effect, which I find very attractive. The necklet at the top of this post has a copper clasp. This is made by winding copper wire tightly around each end of the cord and shaping the wire into a hook on one end and an eye on the other end. To ensure the wite stayed in place, I used a little bit of glue under the wire.

The necklet at the top of this post has a copper clasp. This is made by winding copper wire tightly around each end of the cord and shaping the wire into a hook on one end and an eye on the other end. To ensure the wite stayed in place, I used a little bit of glue under the wire. What do forty-two kilometres of rope used in Nelson’s sailing ship, HMS Victory, a traditional Māori feather cloak, and the Victorian lace collar in the photo all have in common? They’re all made with strong, thin fibres that have been stripped from the leaves of the New Zealand flax plant. For hundreds of years, Māori used this fibre to make clothes, ropes, fishing nets and bird snares. Later, European immigrants developed large-scale rope manufacturing using a stripping machine that could process up to 250 kilograms of fibre a day.

What do forty-two kilometres of rope used in Nelson’s sailing ship, HMS Victory, a traditional Māori feather cloak, and the Victorian lace collar in the photo all have in common? They’re all made with strong, thin fibres that have been stripped from the leaves of the New Zealand flax plant. For hundreds of years, Māori used this fibre to make clothes, ropes, fishing nets and bird snares. Later, European immigrants developed large-scale rope manufacturing using a stripping machine that could process up to 250 kilograms of fibre a day.  Thread stripped from the leaf by hand is a much finer thread than thread stripped by machine. In traditional hand-stripping, a mussel shell is scraped along the length of a strip of flax, forcing the green fleshy outer layer of the leaf down through and away from the fibres, and leaving the fibres clean and clearly separated into individual threads. With machine stripping, the whole leaf is put into a revolving metal drum where wooden paddles beat the green pulp off the fibre. The pulped leaves are then put through a scrutching machine which dresses the fibre by removing the short fibres and cleaning off any remaining particles. However this process doesn’t clean or separate the fibres completely, so machine-made flax thread is thicker and rougher.

Thread stripped from the leaf by hand is a much finer thread than thread stripped by machine. In traditional hand-stripping, a mussel shell is scraped along the length of a strip of flax, forcing the green fleshy outer layer of the leaf down through and away from the fibres, and leaving the fibres clean and clearly separated into individual threads. With machine stripping, the whole leaf is put into a revolving metal drum where wooden paddles beat the green pulp off the fibre. The pulped leaves are then put through a scrutching machine which dresses the fibre by removing the short fibres and cleaning off any remaining particles. However this process doesn’t clean or separate the fibres completely, so machine-made flax thread is thicker and rougher. The difference between fibres produced by hand and those produced by machine became very clear to me while I was preparing a talk on flax weaving for the 2008 conference of the

The difference between fibres produced by hand and those produced by machine became very clear to me while I was preparing a talk on flax weaving for the 2008 conference of the  When making rope or a traditional Māori feather cloak, or in the threads traditionally used for lace-making, the strands of fibre are invariably twisted together to make a thread. This makes the thread stronger and allows new fibres to be twisted in, so that the thread can be much longer than the original fibres. However, after examining Mrs Williams’ work, and experimenting with flax fibre myself, it became clear that Mrs Williams knew what she was doing. Twisted flax fibre is just too thick for lace-making in the traditional method, so her four-strand fibres were limited to the length of the leaves from a flax plant.

When making rope or a traditional Māori feather cloak, or in the threads traditionally used for lace-making, the strands of fibre are invariably twisted together to make a thread. This makes the thread stronger and allows new fibres to be twisted in, so that the thread can be much longer than the original fibres. However, after examining Mrs Williams’ work, and experimenting with flax fibre myself, it became clear that Mrs Williams knew what she was doing. Twisted flax fibre is just too thick for lace-making in the traditional method, so her four-strand fibres were limited to the length of the leaves from a flax plant. Have you ever noticed that dyed flax often loses some of the natural sheen that can be seen on freshly harvested flax, leaving the colour flat and dull? It seems that the sheen comes from a layer of wax on the surface of the flax leaf. Apparently, all plant leaves have at least some wax on the surface of their leaves — mainly to waterproof them but also to provide a degree of protection from the sun’s ultraviolet rays, and from disease and grazing by insects.

Have you ever noticed that dyed flax often loses some of the natural sheen that can be seen on freshly harvested flax, leaving the colour flat and dull? It seems that the sheen comes from a layer of wax on the surface of the flax leaf. Apparently, all plant leaves have at least some wax on the surface of their leaves — mainly to waterproof them but also to provide a degree of protection from the sun’s ultraviolet rays, and from disease and grazing by insects. For the long list of people who have asked to be notified as soon as the booklet comes out, and have been waiting patiently, in many cases for several months, I must apologise once again. There are several reasons for the delay. Firstly, I’ve been including more and more weaving designs for flowers, and improving the photography and layout as I’ve gone along. Secondly, I recently moved from my well-established lifestyle block in the country to the city, and the move has taken up quite some time. Thirdly, having finished working on the instructions, it seemed silly to release the booklet without showing at least some examples of what can be done with the flax flowers once they’ve been woven.

For the long list of people who have asked to be notified as soon as the booklet comes out, and have been waiting patiently, in many cases for several months, I must apologise once again. There are several reasons for the delay. Firstly, I’ve been including more and more weaving designs for flowers, and improving the photography and layout as I’ve gone along. Secondly, I recently moved from my well-established lifestyle block in the country to the city, and the move has taken up quite some time. Thirdly, having finished working on the instructions, it seemed silly to release the booklet without showing at least some examples of what can be done with the flax flowers once they’ve been woven. The top edge of a kete can be finished in many different ways and the one you choose will depend on the look you’d like for your kete. In this little kete I wanted undyed variegated flax to be the main feature, and this already made the design a bit busy, so I used a simple straight edge on the top. (Incidentally, although the colour of variegated flax will fade, the variations in tone will still be visible when it is faded).

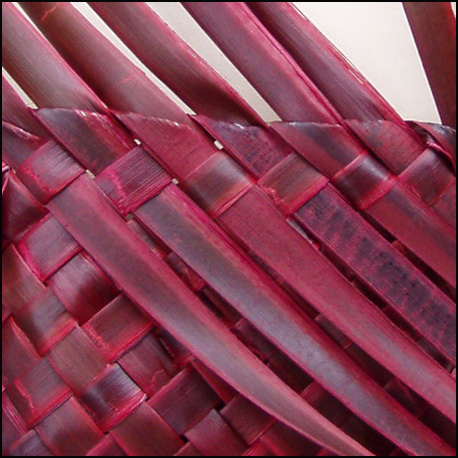

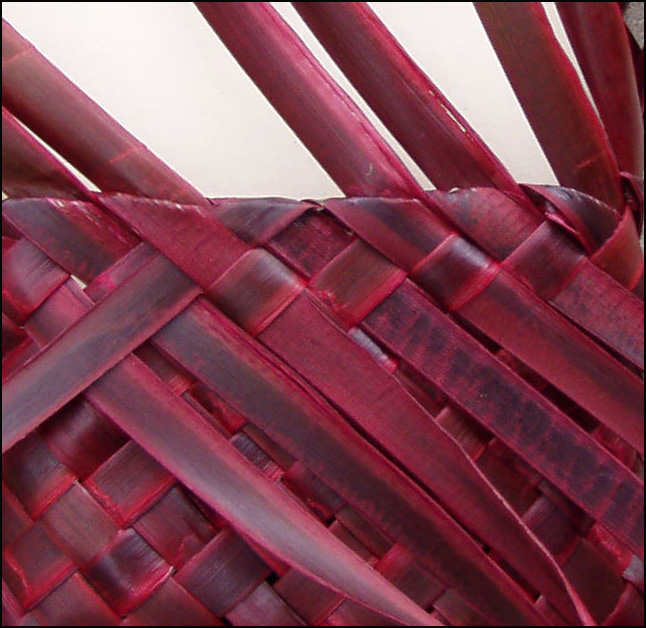

The top edge of a kete can be finished in many different ways and the one you choose will depend on the look you’d like for your kete. In this little kete I wanted undyed variegated flax to be the main feature, and this already made the design a bit busy, so I used a simple straight edge on the top. (Incidentally, although the colour of variegated flax will fade, the variations in tone will still be visible when it is faded).

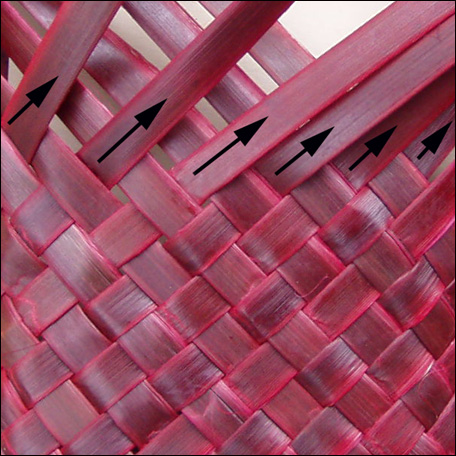

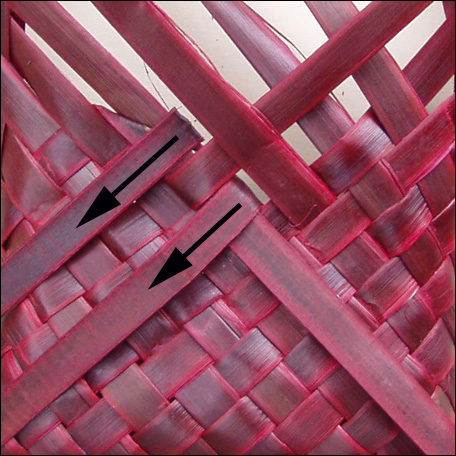

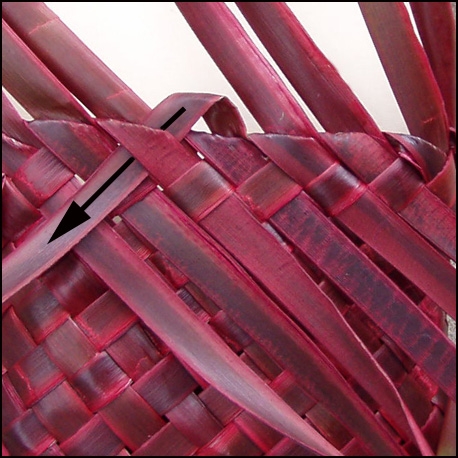

Weave the kete to the height you want it. Start the straight edge by folding one of the top strips that is pointing up to the right, back on itself, so that it is lying pointing downwards to the left. Miss one strip along the top edge and take the next strip pointing up to the right, pull it out from underneath the strip it is lying under and fold it back down across the same strip that the first one is folded down on. The strip that is pointing up to the left is now lying alongside the fold of the second strip that was folded back, over the strip that was missed and alongside the fold of the first strip that was folded back.

Weave the kete to the height you want it. Start the straight edge by folding one of the top strips that is pointing up to the right, back on itself, so that it is lying pointing downwards to the left. Miss one strip along the top edge and take the next strip pointing up to the right, pull it out from underneath the strip it is lying under and fold it back down across the same strip that the first one is folded down on. The strip that is pointing up to the left is now lying alongside the fold of the second strip that was folded back, over the strip that was missed and alongside the fold of the first strip that was folded back.

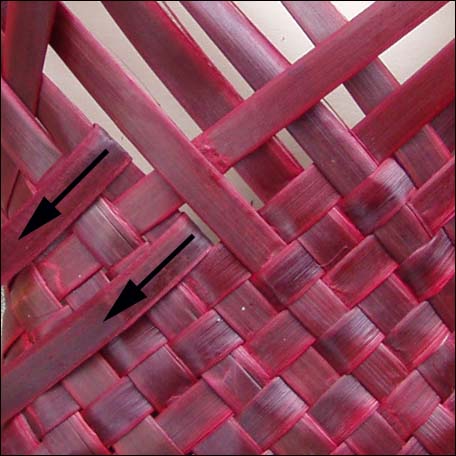

Bring the first strip, that was folded back, forward again and then bend it downwards at an angle to the right so that it lies over the top of the strip pointing up to the left. Bring the second strip, that was folded back, up again to lock this strip in place. You will repeat this set of steps right around the top.

Bring the first strip, that was folded back, forward again and then bend it downwards at an angle to the right so that it lies over the top of the strip pointing up to the left. Bring the second strip, that was folded back, up again to lock this strip in place. You will repeat this set of steps right around the top.

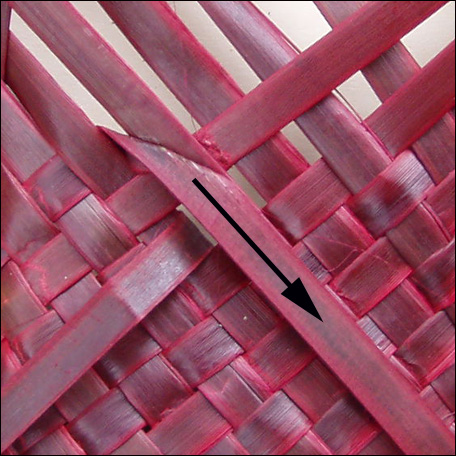

Start the next set of steps by folding back the next top strip, and the third one along, as in the first step. Continue with the rest of the steps. Then repeat this set of steps until you come back to the beginning. The first part of the straight edge is now finished. The strips you have folded down have formed a straight edge around the kete and there will be strips pointing up to the left all the way around.

Start the next set of steps by folding back the next top strip, and the third one along, as in the first step. Continue with the rest of the steps. Then repeat this set of steps until you come back to the beginning. The first part of the straight edge is now finished. The strips you have folded down have formed a straight edge around the kete and there will be strips pointing up to the left all the way around.

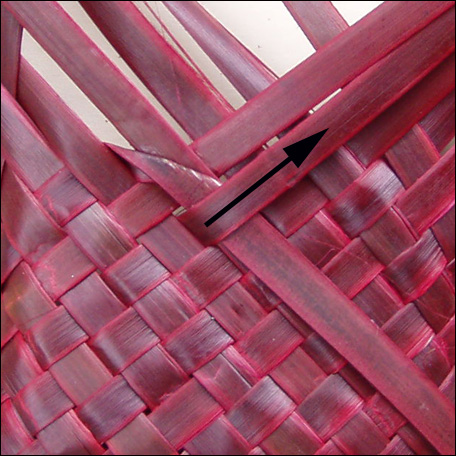

The strips lying up to the left now need to be woven back down into the body of the kete. Take one of these strips and fold it down to the left, over the fold of the strip in front of it, and then thread it underneath the strip next to this one. Thread the strip down one more time through the next available strip.

The strips lying up to the left now need to be woven back down into the body of the kete. Take one of these strips and fold it down to the left, over the fold of the strip in front of it, and then thread it underneath the strip next to this one. Thread the strip down one more time through the next available strip.  Complete this all the way around the top of the kete. Finish by simply cutting the ends off, or embellish the kete by fringing the ends or plaiting them around the kete.

Complete this all the way around the top of the kete. Finish by simply cutting the ends off, or embellish the kete by fringing the ends or plaiting them around the kete.