26 May 2008

What do forty-two kilometres of rope used in Nelson’s sailing ship, HMS Victory, a traditional Māori feather cloak, and the Victorian lace collar in the photo all have in common? They’re all made with strong, thin fibres that have been stripped from the leaves of the New Zealand flax plant. For hundreds of years, Māori used this fibre to make clothes, ropes, fishing nets and bird snares. Later, European immigrants developed large-scale rope manufacturing using a stripping machine that could process up to 250 kilograms of fibre a day.

What do forty-two kilometres of rope used in Nelson’s sailing ship, HMS Victory, a traditional Māori feather cloak, and the Victorian lace collar in the photo all have in common? They’re all made with strong, thin fibres that have been stripped from the leaves of the New Zealand flax plant. For hundreds of years, Māori used this fibre to make clothes, ropes, fishing nets and bird snares. Later, European immigrants developed large-scale rope manufacturing using a stripping machine that could process up to 250 kilograms of fibre a day.

Thread stripped from the leaf by hand is a much finer thread than thread stripped by machine. In traditional hand-stripping, a mussel shell is scraped along the length of a strip of flax, forcing the green fleshy outer layer of the leaf down through and away from the fibres, and leaving the fibres clean and clearly separated into individual threads. With machine stripping, the whole leaf is put into a revolving metal drum where wooden paddles beat the green pulp off the fibre. The pulped leaves are then put through a scrutching machine which dresses the fibre by removing the short fibres and cleaning off any remaining particles. However this process doesn’t clean or separate the fibres completely, so machine-made flax thread is thicker and rougher.

Thread stripped from the leaf by hand is a much finer thread than thread stripped by machine. In traditional hand-stripping, a mussel shell is scraped along the length of a strip of flax, forcing the green fleshy outer layer of the leaf down through and away from the fibres, and leaving the fibres clean and clearly separated into individual threads. With machine stripping, the whole leaf is put into a revolving metal drum where wooden paddles beat the green pulp off the fibre. The pulped leaves are then put through a scrutching machine which dresses the fibre by removing the short fibres and cleaning off any remaining particles. However this process doesn’t clean or separate the fibres completely, so machine-made flax thread is thicker and rougher.

The difference between fibres produced by hand and those produced by machine became very clear to me while I was preparing a talk on flax weaving for the 2008 conference of the New Zealand Lace Society. I thought lace-makers might find it interesting if the talk included a demonstration of lace-making with flax fibre, even though I hadn’t tried this before. However, I’d had plenty of experience with linen and cotton fibre because I used to be heavily involved in lace-making and the NZ Lace Society. So the talk was a good chance to catch up with old friends — and I also caught up with a participant of my flax-weaving workshops who had used flax fibre she had stripped by hand to make an award-winning entry in this years’ lace competition.

The difference between fibres produced by hand and those produced by machine became very clear to me while I was preparing a talk on flax weaving for the 2008 conference of the New Zealand Lace Society. I thought lace-makers might find it interesting if the talk included a demonstration of lace-making with flax fibre, even though I hadn’t tried this before. However, I’d had plenty of experience with linen and cotton fibre because I used to be heavily involved in lace-making and the NZ Lace Society. So the talk was a good chance to catch up with old friends — and I also caught up with a participant of my flax-weaving workshops who had used flax fibre she had stripped by hand to make an award-winning entry in this years’ lace competition.

As well as giving a demonstration, I wanted to give the participants the opportunity to have a go at making bobbin lace with flax fibre themselves. I already had some machine-made flax fibre that I’d purchased from the Templeton Flaxmill Museum near Riverton, but this proved to be just too irregular and thick to wind easily on lace bobbins, so I prepared the flax fibre by hand. Although fibre can be stripped from many different varieties of Phormium tenax, I wanted to use the very best varieties, so I approached the National New Zealand Flax Collection at Landcare Research in Lincoln and received permission to gather leaves from two of the traditional weaving flaxes, Arawa and Makewero, that are both known for their long, clean fibres. I stripped the leaves in the traditional Māori way — with a mussel shell — for the first time, and have just updated my Preparing flax page with a some tips on the difference between stripping flax with a mussel shell and a blunt knife.

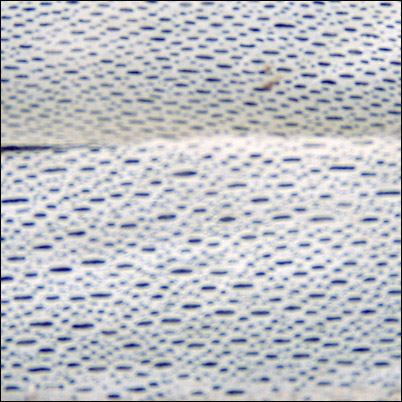

Before setting up the lace pillows for lace-making with the flax fibre, I examined the lace collar shown at the beginning of this post. This formed the subject of a talk at the conference by Jennifer Quérée, Senior Curator of Decorative Arts at the Canterbury Museum. The collar was made by a Mrs Williams, and it received a special mention at the 1906 New Zealand International Exhibition. I noticed that it was woven with four strands of flax fibre per thread, and that the fibres hadn’t been twisted to make the thread.

When making rope or a traditional Māori feather cloak, or in the threads traditionally used for lace-making, the strands of fibre are invariably twisted together to make a thread. This makes the thread stronger and allows new fibres to be twisted in, so that the thread can be much longer than the original fibres. However, after examining Mrs Williams’ work, and experimenting with flax fibre myself, it became clear that Mrs Williams knew what she was doing. Twisted flax fibre is just too thick for lace-making in the traditional method, so her four-strand fibres were limited to the length of the leaves from a flax plant.

When making rope or a traditional Māori feather cloak, or in the threads traditionally used for lace-making, the strands of fibre are invariably twisted together to make a thread. This makes the thread stronger and allows new fibres to be twisted in, so that the thread can be much longer than the original fibres. However, after examining Mrs Williams’ work, and experimenting with flax fibre myself, it became clear that Mrs Williams knew what she was doing. Twisted flax fibre is just too thick for lace-making in the traditional method, so her four-strand fibres were limited to the length of the leaves from a flax plant.

For the demonstration, I set up one lace pillow with the bobbins wound with four strands per thread, and another pillow with bobbins wound with a single strand per thread. Participants who tried weaving lace with the four-strand bobbins found it quite difficult. The single-strand bobbins were easier to work with, but — compared with the threads traditionally used for lace-making — flax fibre is quite stiff and isn’t as slippery, so this makes it harder to tension the weaving. Also, each single fibre is made up of even finer strands which tends to make the thread quite fluffy.

All in all, it it became clear to all of us that Mrs Williams’ collar must have been a very challenging piece of work, and — like a traditional Māori feather cloak — it would also have taken rather a long time to weave.

Errata 3 Jun 2008

Since I first wrote this post I’ve made two corrections in it in light of Jennifer Quérée’s comment in the earlier-comments link below — the lace collar was made by a Mrs Williams, and I originally referred to her as Mrs Williamson. Also, the collar received a special mention at the Exhibition but didn’t win an award. Jennifer’s comment provides additional information on the collar.

© Ali Brown 2008.

Scroll down to leave a new comment or view recent comments.

Also, check out earlier comments received on this blog post when it was hosted on my original website.

Have you ever noticed that dyed flax often loses some of the natural sheen that can be seen on freshly harvested flax, leaving the colour flat and dull? It seems that the sheen comes from a layer of wax on the surface of the flax leaf. Apparently, all plant leaves have at least some wax on the surface of their leaves — mainly to waterproof them but also to provide a degree of protection from the sun’s ultraviolet rays, and from disease and grazing by insects.

Have you ever noticed that dyed flax often loses some of the natural sheen that can be seen on freshly harvested flax, leaving the colour flat and dull? It seems that the sheen comes from a layer of wax on the surface of the flax leaf. Apparently, all plant leaves have at least some wax on the surface of their leaves — mainly to waterproof them but also to provide a degree of protection from the sun’s ultraviolet rays, and from disease and grazing by insects. For the long list of people who have asked to be notified as soon as the booklet comes out, and have been waiting patiently, in many cases for several months, I must apologise once again. There are several reasons for the delay. Firstly, I’ve been including more and more weaving designs for flowers, and improving the photography and layout as I’ve gone along. Secondly, I recently moved from my well-established lifestyle block in the country to the city, and the move has taken up quite some time. Thirdly, having finished working on the instructions, it seemed silly to release the booklet without showing at least some examples of what can be done with the flax flowers once they’ve been woven.

For the long list of people who have asked to be notified as soon as the booklet comes out, and have been waiting patiently, in many cases for several months, I must apologise once again. There are several reasons for the delay. Firstly, I’ve been including more and more weaving designs for flowers, and improving the photography and layout as I’ve gone along. Secondly, I recently moved from my well-established lifestyle block in the country to the city, and the move has taken up quite some time. Thirdly, having finished working on the instructions, it seemed silly to release the booklet without showing at least some examples of what can be done with the flax flowers once they’ve been woven. The top edge of a kete can be finished in many different ways and the one you choose will depend on the look you’d like for your kete. In this little kete I wanted undyed variegated flax to be the main feature, and this already made the design a bit busy, so I used a simple straight edge on the top. (Incidentally, although the colour of variegated flax will fade, the variations in tone will still be visible when it is faded).

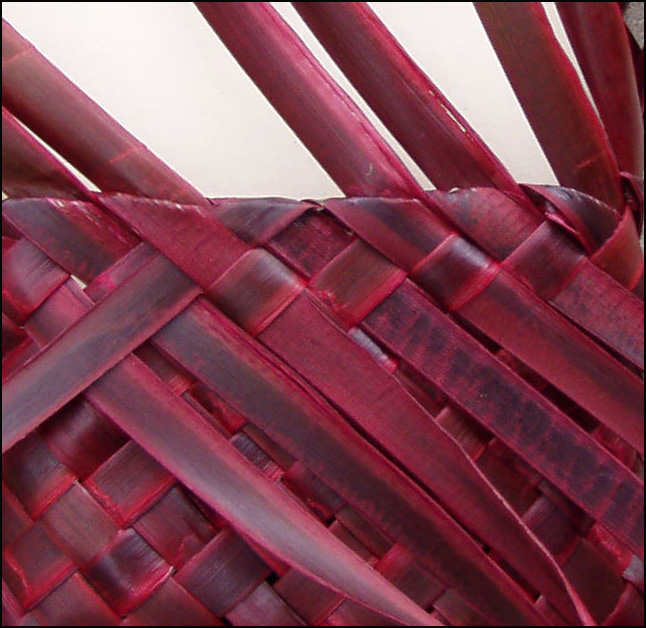

The top edge of a kete can be finished in many different ways and the one you choose will depend on the look you’d like for your kete. In this little kete I wanted undyed variegated flax to be the main feature, and this already made the design a bit busy, so I used a simple straight edge on the top. (Incidentally, although the colour of variegated flax will fade, the variations in tone will still be visible when it is faded).

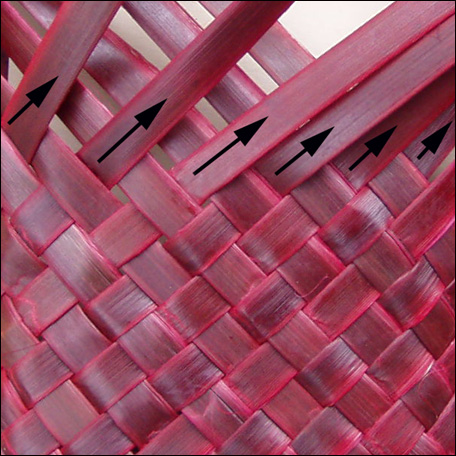

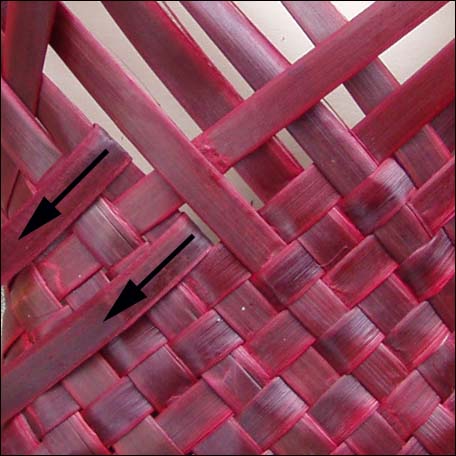

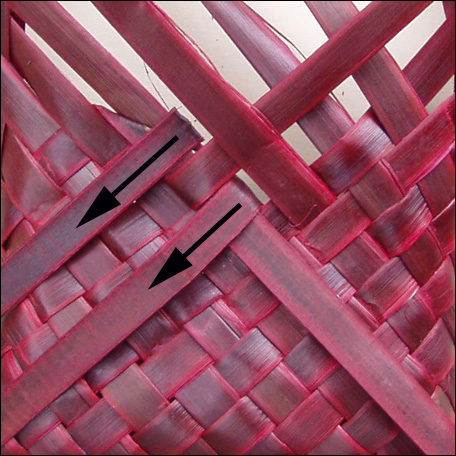

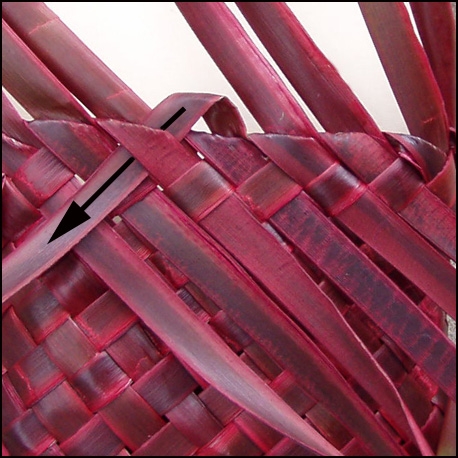

Weave the kete to the height you want it. Start the straight edge by folding one of the top strips that is pointing up to the right, back on itself, so that it is lying pointing downwards to the left. Miss one strip along the top edge and take the next strip pointing up to the right, pull it out from underneath the strip it is lying under and fold it back down across the same strip that the first one is folded down on. The strip that is pointing up to the left is now lying alongside the fold of the second strip that was folded back, over the strip that was missed and alongside the fold of the first strip that was folded back.

Weave the kete to the height you want it. Start the straight edge by folding one of the top strips that is pointing up to the right, back on itself, so that it is lying pointing downwards to the left. Miss one strip along the top edge and take the next strip pointing up to the right, pull it out from underneath the strip it is lying under and fold it back down across the same strip that the first one is folded down on. The strip that is pointing up to the left is now lying alongside the fold of the second strip that was folded back, over the strip that was missed and alongside the fold of the first strip that was folded back.

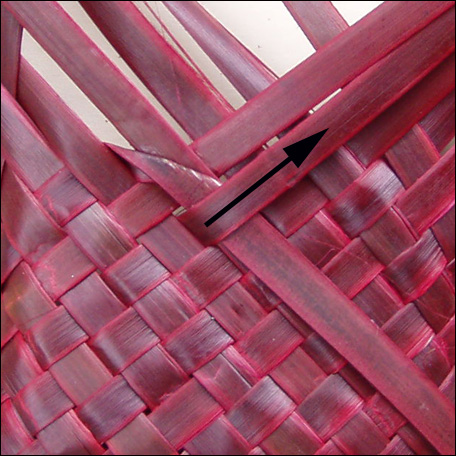

Bring the first strip, that was folded back, forward again and then bend it downwards at an angle to the right so that it lies over the top of the strip pointing up to the left. Bring the second strip, that was folded back, up again to lock this strip in place. You will repeat this set of steps right around the top.

Bring the first strip, that was folded back, forward again and then bend it downwards at an angle to the right so that it lies over the top of the strip pointing up to the left. Bring the second strip, that was folded back, up again to lock this strip in place. You will repeat this set of steps right around the top.

Start the next set of steps by folding back the next top strip, and the third one along, as in the first step. Continue with the rest of the steps. Then repeat this set of steps until you come back to the beginning. The first part of the straight edge is now finished. The strips you have folded down have formed a straight edge around the kete and there will be strips pointing up to the left all the way around.

Start the next set of steps by folding back the next top strip, and the third one along, as in the first step. Continue with the rest of the steps. Then repeat this set of steps until you come back to the beginning. The first part of the straight edge is now finished. The strips you have folded down have formed a straight edge around the kete and there will be strips pointing up to the left all the way around.

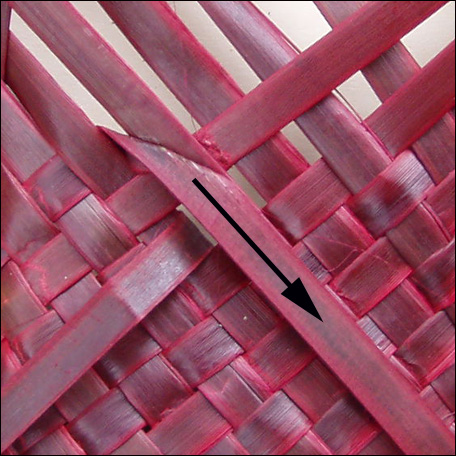

The strips lying up to the left now need to be woven back down into the body of the kete. Take one of these strips and fold it down to the left, over the fold of the strip in front of it, and then thread it underneath the strip next to this one. Thread the strip down one more time through the next available strip.

The strips lying up to the left now need to be woven back down into the body of the kete. Take one of these strips and fold it down to the left, over the fold of the strip in front of it, and then thread it underneath the strip next to this one. Thread the strip down one more time through the next available strip.  Complete this all the way around the top of the kete. Finish by simply cutting the ends off, or embellish the kete by fringing the ends or plaiting them around the kete.

Complete this all the way around the top of the kete. Finish by simply cutting the ends off, or embellish the kete by fringing the ends or plaiting them around the kete.  Have fun with gift wrapping by using flax for decoration on your gifts! Shredded flax is great for ties, flax stars with curled flax ribbons are an ideal decoration for Christmas gifts and, of course, flax flowers are an appealing addition to any gift.

Have fun with gift wrapping by using flax for decoration on your gifts! Shredded flax is great for ties, flax stars with curled flax ribbons are an ideal decoration for Christmas gifts and, of course, flax flowers are an appealing addition to any gift. To make a star with flax, you will need four strips of flax about one centimetre wide and thirty centimetres long. If you want to tie the ends around a parcel, once you’ve made the star, you’ll need to make the strips as long as possible. Soften the strips by scraping a knife along the underside (dull side) of the strips and then lay them together in pairs and use the pairs as if they were one strip for now. Wrap the first strip around your fingers and keep a loop at the top. Hold this in place with your thumb or it can be held in place with a peg.

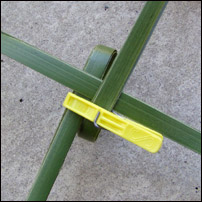

To make a star with flax, you will need four strips of flax about one centimetre wide and thirty centimetres long. If you want to tie the ends around a parcel, once you’ve made the star, you’ll need to make the strips as long as possible. Soften the strips by scraping a knife along the underside (dull side) of the strips and then lay them together in pairs and use the pairs as if they were one strip for now. Wrap the first strip around your fingers and keep a loop at the top. Hold this in place with your thumb or it can be held in place with a peg.  Place the second pair of strips horizontally across in front of the looped strip and behind the strip that is pointing upwards.

Place the second pair of strips horizontally across in front of the looped strip and behind the strip that is pointing upwards. Take the end of the strip that is pointing out to the left back around behind the loop, across in front of the strip pointing upwards and then poke it through the loop.

Take the end of the strip that is pointing out to the left back around behind the loop, across in front of the strip pointing upwards and then poke it through the loop. Tighten the weaving by pulling each set of ends in the direction they are pointing so that there is now a woven square.

Tighten the weaving by pulling each set of ends in the direction they are pointing so that there is now a woven square. Turn the woven square over and hold the weaving so that the strip on top of the two in the middle of the square is lying with the top on the right and the bottom on the left.

Turn the woven square over and hold the weaving so that the strip on top of the two in the middle of the square is lying with the top on the right and the bottom on the left. Take one strip of the two strips lying together at the top and fold it down on itself.

Take one strip of the two strips lying together at the top and fold it down on itself. Continue folding down one strip on itself in an anti-clockwise direction around the square. Secure all these by poking the last strip under the first strip that was folded down. The woven square now has two strips coming out from each side.

Continue folding down one strip on itself in an anti-clockwise direction around the square. Secure all these by poking the last strip under the first strip that was folded down. The woven square now has two strips coming out from each side. Take the right strip of the two at the top and fold it behind and across to the right and then forward and down.

Take the right strip of the two at the top and fold it behind and across to the right and then forward and down. Fold the strip back on itself to create a point and secure this by poking the end back down underneath the strip where it came out from, making sure you don’t pull too far so that the point is pulled right through.

Fold the strip back on itself to create a point and secure this by poking the end back down underneath the strip where it came out from, making sure you don’t pull too far so that the point is pulled right through. Repeat this and make a point on the other three right-hand strips.

Repeat this and make a point on the other three right-hand strips. Turn the star over and make points on the other four strips, only this time fold the strip forward and across and then down, rather than behind and across as before.

Turn the star over and make points on the other four strips, only this time fold the strip forward and across and then down, rather than behind and across as before.  There will now be four ends coming out from each side of the star. Cut the ends off closely and the star is ready to attach to the gift. If you want to use the ends to tie the star to a parcel, cut off only one set of ends.

There will now be four ends coming out from each side of the star. Cut the ends off closely and the star is ready to attach to the gift. If you want to use the ends to tie the star to a parcel, cut off only one set of ends. To curl flax, wind it tightly around a dowel or similar while it is still fresh and green, or still wet after being dyed. Then leave it to dry. The flax will then be set in place in curls.

To curl flax, wind it tightly around a dowel or similar while it is still fresh and green, or still wet after being dyed. Then leave it to dry. The flax will then be set in place in curls. I ran my first flax weaving workshop for “at-risk” teenagers last weekend, and was a little nervous before the workshop, because I wasn’t sure that all the participants were coming to the workshop entirely of their own free will, and if they weren’t it might have made for an uneasy atmosphere. I needn’t have worried. It went off well and all the participants appeared to enjoy themselves.

I ran my first flax weaving workshop for “at-risk” teenagers last weekend, and was a little nervous before the workshop, because I wasn’t sure that all the participants were coming to the workshop entirely of their own free will, and if they weren’t it might have made for an uneasy atmosphere. I needn’t have worried. It went off well and all the participants appeared to enjoy themselves.  The wristbands are made with a strip of flax which is long enough to go around a wrist four times. Prepare this strip about 2 cm wide and as long as it can go without using the thicker white butt end of the strip. Soften the strip before using it by placing the blunt edge of a knife against the dull side of the flax strip (the underside of the leaf) about halfway along the length of the strip. Hold the strip against the knife with your thumb, and pull the strip through on about a 90 degree angle to the knife. Scrape the flax in each direction, pulling to the end of the strip each way.

The wristbands are made with a strip of flax which is long enough to go around a wrist four times. Prepare this strip about 2 cm wide and as long as it can go without using the thicker white butt end of the strip. Soften the strip before using it by placing the blunt edge of a knife against the dull side of the flax strip (the underside of the leaf) about halfway along the length of the strip. Hold the strip against the knife with your thumb, and pull the strip through on about a 90 degree angle to the knife. Scrape the flax in each direction, pulling to the end of the strip each way.  Wind the cut end of the strip around twice into a circle that is just big enough to fit over a hand. Secure the strip at this point with some tape. Split the free end into strips of an even width and make two extra strips that are the same width as these strips. These will be used to weave through the three strips of the main wristband.

Wind the cut end of the strip around twice into a circle that is just big enough to fit over a hand. Secure the strip at this point with some tape. Split the free end into strips of an even width and make two extra strips that are the same width as these strips. These will be used to weave through the three strips of the main wristband.  The simple wristband pictured here shows the circular strip split into three strips of the same width, with a separate weaving strip of the same width laid across them, going over the outer strips and underneath the middle one. Take one of the narrower strips and hold it with the thicker end out to the left. Position it under the middle strip of the three strips on the wristband. Leave about 10 cm poking out to the left and with the long length of the strip poking out to the right.

The simple wristband pictured here shows the circular strip split into three strips of the same width, with a separate weaving strip of the same width laid across them, going over the outer strips and underneath the middle one. Take one of the narrower strips and hold it with the thicker end out to the left. Position it under the middle strip of the three strips on the wristband. Leave about 10 cm poking out to the left and with the long length of the strip poking out to the right.

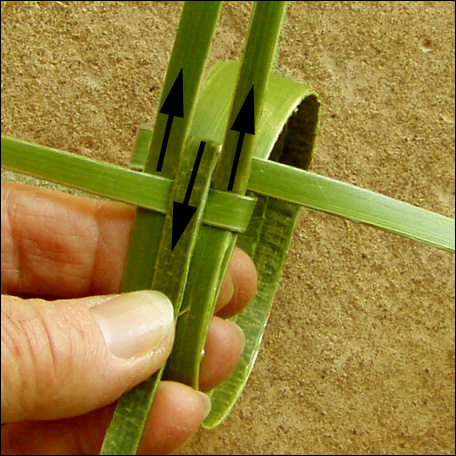

As shown on the left, fold back the two outer strips over the top of the weaving strip, then hold them down with your thumb. As shown on the right, pass the end of the weaving strip through the middle of the wristband.

As shown on the left, fold back the two outer strips over the top of the weaving strip, then hold them down with your thumb. As shown on the right, pass the end of the weaving strip through the middle of the wristband.

As shown on the left, bring the weaving strip back around to the front and lay it across the top again, over the middle strip. As shown on the right, fold the two outer strips forward over the weaving strip, which is the strip pointing out to the right, and then fold the middle strip back, and hold it down with your thumb. (The end of the strip pointing out to the left is the start of the weaving strip and is not being used for weaving.)

As shown on the left, bring the weaving strip back around to the front and lay it across the top again, over the middle strip. As shown on the right, fold the two outer strips forward over the weaving strip, which is the strip pointing out to the right, and then fold the middle strip back, and hold it down with your thumb. (The end of the strip pointing out to the left is the start of the weaving strip and is not being used for weaving.)

Continue taking the weaving strip through the middle of the wristband and bringing it around over the top, while moving the central strips back and forwards. When the weaving strip gets short, lay a new strip over the top of the first strip and then use the new strip for weaving.

Continue taking the weaving strip through the middle of the wristband and bringing it around over the top, while moving the central strips back and forwards. When the weaving strip gets short, lay a new strip over the top of the first strip and then use the new strip for weaving. When the strips have been woven all the way around, weave the ends of the strips into the start of the wristband. Thread any other ends through the inside of the wristband and cut them off. If the wristband is not quite circular, push it down over a glass or jar until it fits tightly. This will help it dry into a circular shape.

When the strips have been woven all the way around, weave the ends of the strips into the start of the wristband. Thread any other ends through the inside of the wristband and cut them off. If the wristband is not quite circular, push it down over a glass or jar until it fits tightly. This will help it dry into a circular shape. People regularly ask me if it’s possible to take flaxworks into other countries and the short answer is ‘yes’, although I recommend that flaxworks are declared as you go through customs.

People regularly ask me if it’s possible to take flaxworks into other countries and the short answer is ‘yes’, although I recommend that flaxworks are declared as you go through customs. Weaving a flax belt is reasonably straightforward — a first-time weaver completed a belt on the second day of a workshop I tutored last weekend. Using the same basic pattern, it would be easy enough to add your own modifications and create a unique item.

Weaving a flax belt is reasonably straightforward — a first-time weaver completed a belt on the second day of a workshop I tutored last weekend. Using the same basic pattern, it would be easy enough to add your own modifications and create a unique item.  To make the belt, use flax strips about .8 cm wide. Prepare twenty strips (ten more if the flax you are using is short in length) as extra strips will be added in when the ends of the original strips are nearly reached. Start by twining ten strips together in a row and then weaving up. Fold the strips over at the end of the rows instead of twisting them. This makes a neat edge although both sides of the flax will show in stages along the belt’s length. Add a new strip when there is about 10cm left of the old one. Weave the new strip along with the old one and then continue to weave with the new one as the old one runs out. Weave the length you want for your belt taking into account the space that the bangle will take up.

To make the belt, use flax strips about .8 cm wide. Prepare twenty strips (ten more if the flax you are using is short in length) as extra strips will be added in when the ends of the original strips are nearly reached. Start by twining ten strips together in a row and then weaving up. Fold the strips over at the end of the rows instead of twisting them. This makes a neat edge although both sides of the flax will show in stages along the belt’s length. Add a new strip when there is about 10cm left of the old one. Weave the new strip along with the old one and then continue to weave with the new one as the old one runs out. Weave the length you want for your belt taking into account the space that the bangle will take up. To include the bangle at the end, narrow the weaving by folding two strips each side back into the previous weaving and continue weaving the narrower strip for about three rows. Put the bangle over this and fold the narrow woven piece back along the inside of the belt, threading all the ends for about 5-8cm into the weaving on the inside of the belt — long enough to hold the bangle securely when the belt’s worn. The other end is narrowed in the same way as this end and a buttonhole included after about two rows of weaving. Weave two more rows then fold and thread all the strips back into the narrow strip of weaving to secure the ends. Sew a button onto the inside of the belt.

To include the bangle at the end, narrow the weaving by folding two strips each side back into the previous weaving and continue weaving the narrower strip for about three rows. Put the bangle over this and fold the narrow woven piece back along the inside of the belt, threading all the ends for about 5-8cm into the weaving on the inside of the belt — long enough to hold the bangle securely when the belt’s worn. The other end is narrowed in the same way as this end and a buttonhole included after about two rows of weaving. Weave two more rows then fold and thread all the strips back into the narrow strip of weaving to secure the ends. Sew a button onto the inside of the belt. The format of my two-day workshops has been evolving as I’ve learned more about what first-time weavers are ready to learn on the second day of a two-day workshop. I tutored a two-day workshop at the Christchurch Arts Centre last weekend and, for the first time, I included a session on dyeing flax. Naturally enough, people want to be able to weave with the flax once they have dyed it, and they’re often keen to try out traditional dyed weaving that is geometrically patterned. Unfortunately this requires a construction technique that is perhaps a little too complex to tackle for people who are just beginning to weave — and so to answer the question of “What can I do with the flax now that I’ve dyed it?”, I showed them how the different colours could be mixed simply and semi-randomly in their weaving for interesting effects.

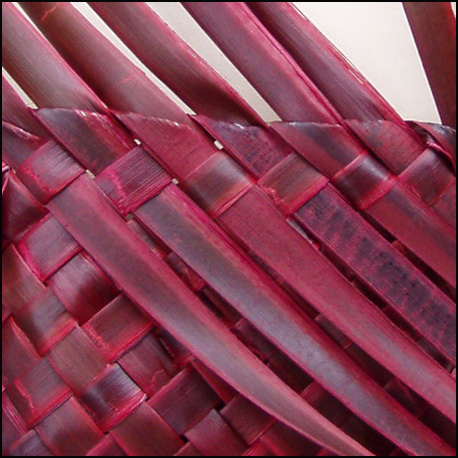

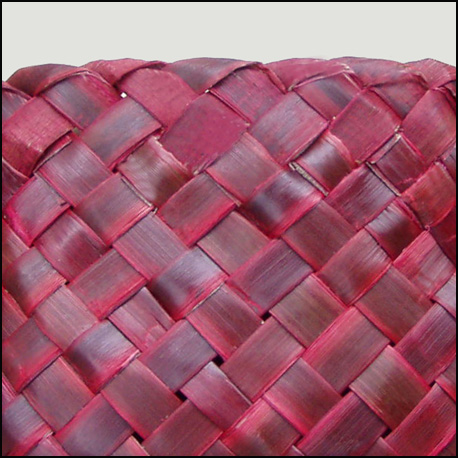

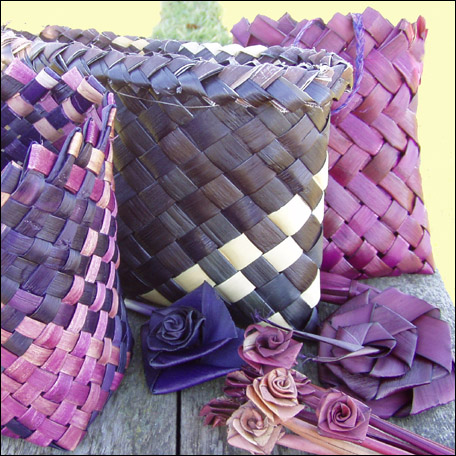

The format of my two-day workshops has been evolving as I’ve learned more about what first-time weavers are ready to learn on the second day of a two-day workshop. I tutored a two-day workshop at the Christchurch Arts Centre last weekend and, for the first time, I included a session on dyeing flax. Naturally enough, people want to be able to weave with the flax once they have dyed it, and they’re often keen to try out traditional dyed weaving that is geometrically patterned. Unfortunately this requires a construction technique that is perhaps a little too complex to tackle for people who are just beginning to weave — and so to answer the question of “What can I do with the flax now that I’ve dyed it?”, I showed them how the different colours could be mixed simply and semi-randomly in their weaving for interesting effects. This worked out well. One person added some undyed strips to mostly black strips for a striking stripe feature in a simple kete. Another, using one colour for the warp strips and a second colour for the weft strips, wove a four-cornered container. Because of the four corners, this placing of colour produces broad blocks of the same colour as the corners are woven and then a combination of a checkerboard and broad blocks of colour as the sides are woven. In the two-cornered kete, this placing of separate colours in the warp and weft produces a complete checkerboard pattern.

This worked out well. One person added some undyed strips to mostly black strips for a striking stripe feature in a simple kete. Another, using one colour for the warp strips and a second colour for the weft strips, wove a four-cornered container. Because of the four corners, this placing of colour produces broad blocks of the same colour as the corners are woven and then a combination of a checkerboard and broad blocks of colour as the sides are woven. In the two-cornered kete, this placing of separate colours in the warp and weft produces a complete checkerboard pattern. Teri dyes were used for the dyeing and the softened flax strips were dyed while they were still fresh and green — although the colour of the dyed flax will be more true to the original colour when using this particular dye if the flax is boiled first. Flax can be also dyed after it has already been woven but the weaving will shrink slightly as it dries so this can result in areas where the full dye colour hasn’t reached the flax at the cross-over of the strips — not such a good look and a method I don’t use for this reason.

Teri dyes were used for the dyeing and the softened flax strips were dyed while they were still fresh and green — although the colour of the dyed flax will be more true to the original colour when using this particular dye if the flax is boiled first. Flax can be also dyed after it has already been woven but the weaving will shrink slightly as it dries so this can result in areas where the full dye colour hasn’t reached the flax at the cross-over of the strips — not such a good look and a method I don’t use for this reason.

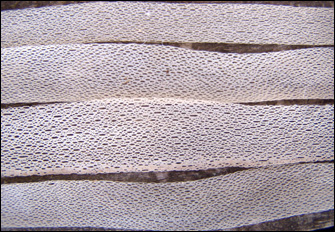

Have you ever wondered where the lacebark tree — a tree with bark that doesn’t look lacey at all — got its name? The answer lies in the layer that is directly underneath the bark, which is the part of the tree that carries the sap. This inner layer of bark in a lacebark tree, or hoheria, and also in the ribbonwood, or manatu, is made up of layers of very thin white strips with many tiny holes that give it a lace-like appearance. These beautiful strips have traditionally been used by Māori for weaving small fine decorative baskets as well as a material for cloaks.

Have you ever wondered where the lacebark tree — a tree with bark that doesn’t look lacey at all — got its name? The answer lies in the layer that is directly underneath the bark, which is the part of the tree that carries the sap. This inner layer of bark in a lacebark tree, or hoheria, and also in the ribbonwood, or manatu, is made up of layers of very thin white strips with many tiny holes that give it a lace-like appearance. These beautiful strips have traditionally been used by Māori for weaving small fine decorative baskets as well as a material for cloaks.  I was recently shown how to harvest the bark on a fallen tree. I’m told bark can also be harvested on a living tree. Ideally, only a small portion of the circumference of the tree is stripped — maybe something like a fifth or a sixth of the circumference — on the north side of the tree on a hot fine day in summer. Apparently, the tree will tolerate this degree of stripping, and can be harvested again in a couple of years’ time.

I was recently shown how to harvest the bark on a fallen tree. I’m told bark can also be harvested on a living tree. Ideally, only a small portion of the circumference of the tree is stripped — maybe something like a fifth or a sixth of the circumference — on the north side of the tree on a hot fine day in summer. Apparently, the tree will tolerate this degree of stripping, and can be harvested again in a couple of years’ time. To get the bark off the trunk, two small vertical cuts are made in the bark and a knife pushed between the core wood and lace bark to start easing it away from the wood. The bark is then pulled up carefully from the tree trunk in a long strip. These strips of bark and inner bark are soaked in water for a few days, which is changed each day, until the inner lace bark starts peeling away from the outer bark and separating out into strips. On the fallen tree the bark can be stripped right down to the core wood although on a living tree the bark is only stripped partially down to the core wood.

To get the bark off the trunk, two small vertical cuts are made in the bark and a knife pushed between the core wood and lace bark to start easing it away from the wood. The bark is then pulled up carefully from the tree trunk in a long strip. These strips of bark and inner bark are soaked in water for a few days, which is changed each day, until the inner lace bark starts peeling away from the outer bark and separating out into strips. On the fallen tree the bark can be stripped right down to the core wood although on a living tree the bark is only stripped partially down to the core wood.